I’ve long been a fan of Alan Kay. We met twenty five years ago as we were building a consulting firm that blended strategic and technology insight. One of Alan’s favorite observations is “point of view is worth 80 IQ points.†Choosing a better vantage point on tough problems is time well spent, especially when there is pressure to get on with it.

I’ve long been a fan of Alan Kay. We met twenty five years ago as we were building a consulting firm that blended strategic and technology insight. One of Alan’s favorite observations is “point of view is worth 80 IQ points.†Choosing a better vantage point on tough problems is time well spent, especially when there is pressure to get on with it.

I’m not sure I can count the number of times I’ve heard or said that we live in a knowledge economy. That we are all knowledge workers who live and work in learning organizations. Yet, we continue to celebrate the industrial revolution in those organizations. We celebrate scale and growth and control. We worry about the problems of accelerating change but assume that working harder and longer will suffice to keep pace.

There is a better vantage point. It is to treat knowledge work as craft work in a technological matrix. Craft work integrates materials, tools, and practices to create artifacts that simultaneously embody the skill and expertise of crafters and meet the practical and esthetic needs of patrons.

Examining each of those elements from a craft perspective illuminates what it takes to become effective as a knowledge worker and remain so as change continues to accumulate. It’s our 80 IQ point move.

Materials – make them visible to make them manageable

Industrial work is built on repeatability; my iPhone 6 Plus is fundamentally identical to yours; any differences are cosmetic. Give me the same consulting report you prepared for your last client and we have a problem. The output of knowledge work derives value by being unique.

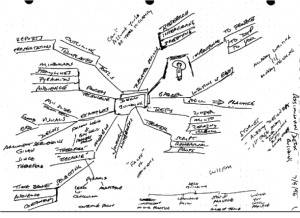

Knowledge work produces highly refined abstractions; a financial analysis, a project plan, a consulting report, a manuscript, or an article. A piece of knowledge work evolves from germ of an idea through multiple, intermediate representations and false starts to finished product. Today, that evolution occurs as a series of morphing digital representations which are difficult to observe and, therefore, difficult to manage and control.

A pre-digital counterexample reveals the unexpected challenges of digital work. I started consulting before the advent of the PC. When you had a presentation to prepare for a client, you began with a pad of paper and a pencil and sketched a set of slides. Erasures and cross outs and arrows made it evident you were working with a draft.

This might be two weeks before the deadline. You took that draft to Evelyn in the graphics department on the eighth floor. After she yelled at you for how little lead time you had given her, she handed your messy and marginally legible draft to one of the commercial artists in her group. They spent several days hand-lettering your draft and building the graphs and charts. They sent you a copy of their work, not being foolish enough to share their originals.

Then the process of correcting and amending the presentation followed. Copies circulated and were marked up by the manager and partner on the project. The graphics department prepared a final version. Finally, the client got to see it and you hoped you’d gotten it right.

Throughout this process, the work was visible. Junior members of the team could learn as the process unfolded and the final product evolved. You, as a consultant, could see how different editors and commentators reacted to different parts of the product.

Today’s digital tools make the journey from idea to finished product easier in many respects. When knowledge artifacts are digital, however, they are hard to see as they develop.

So what? Only the final product matters, right? What possible value is there to the intermediate versions or the component elements? Let’s return to the bygone world of paper again. Malcolm Gladwell offers an interesting observation in “The Social Life of Information:â€

â€But why do we pile documents instead of filing them? Because piles represent the process of active, ongoing thinking. The psychologist Alison Kidd, whose research Sellen and Harper refer to extensively, argues that “knowledge workers” use the physical space of the desktop to hold “ideas which they cannot yet categorize or even decide how they might use.” The messy desk is not necessarily a sign of disorganization. It may be a sign of complexity: those who deal with many unresolved ideas simultaneously cannot sort and file the papers on their desks, because they haven’t yet sorted and filed the ideas in their head. Kidd writes that many of the people she talked to use the papers on their desks as contextual cues to “recover a complex set of threads without difficulty and delay” when they come in on a Monday morning, or after their work has been interrupted by a phone call. What we see when we look at the piles on our desks is, in a sense, the contents of our brains.”

I have friends whose digital desktops have that look about them but this strategy doesn’t readily translate to the digital realm. The physicality of paper gave us version control and audit trails as a free byproduct.

Digital tools promote a focus on final product and divert attention from the work that goes into developing that product. “Track changes†and digital Post-It notes provide inadequate support to the process that proceeds the product. Project teams employ crude naming practices in lieu of substantive version control. Software developers and some research academics have given thought to the problems of how to manage the materials that go into digital knowledge artifacts. Average knowledge workers have yet to do the same.

Visibility is the starting point. Once you make the work observable, you can make it improvable. Concepts like working papers, and audit trails, and personal knowledge management can then come into play.

Tools – Every Day Carry and Well-Equipped Digital Workshops

Where craft matters, so do tools. That got lost in the industrial revolution. Tools were carved out and attached to minute pieces of process, not to the people who wielded them with skill. Meanwhile, the raw materials of knowledge work–words, numbers, and images–did not call for much in the way of tools other than pencil and paper. Mark Twain was an innovator in adopting the typewriter to improve the quantity and quality of his output. But the mechanical tools for aiding knowledge work came to be seen as beneath the dignity of important people.

There was a time when “computers†were women charged with carrying out the menial tasks of doing the calculations men designed and oversaw. It was not that long ago when executives thought it perfectly sensible to have their email printed out and prepare their responses by hand. These attitudes interfere with our abilities to be fully effective doing knowledge work in a digital world.

There’s the old saw that to a child with a hammer, everything looks like a nail. To a skilled cabinet maker, every problem suggests a matching hammer. A well-equipped workshop might contain dozens of different types of hammers, each suited to working with particular materials or in specific situations.

If our materials are digital, then our skill with digital tools becomes a manageable aspect of our working life.

There’s a useful distinction between basic and specialty tools. A basic tool in hand beats the perfect tool back in the shop or office. I’ve carried a pocket knife since my days as a stage manager in college. Courtesy of the TSA I have to remember to leave it behind when I fly or surrender it to the gods of security theater but every other day it’s in my pocket. There is, in fact, an entire subculture devoted to discussions of what constitutes an appropriate EDC—Every Day Carry—for various occupations and environments.

In the realm of knowledge work, Every Day Carry defaults to an email client, calendar, contact manager, word processor, and spreadsheet. For most knowledge workers, tool thinking stops here. Other than software engineers and data scientists, few knowledge workers give much thought to their tools or their effective leverage. Organizations ignore the question of whether knowledge workers are proficient with their tools

If you are judged on the quality of the artifacts that you produce, you would do well to worry about your proficiency with tools. If you have control over your technology environment, set aside time to extend your toolset and learn to use it more effectively. Invest time and thought into how to design, organize, and take advantage of a knowledge workshop filled with the tools of your digital trade. Plan for a mix of EDC, heavy duty, and experimental knowledge work tools.

Practices – Design Effective Habits

Process thinking built the industrial economy. To deliver consistent quality product, variation is designed out and all the steps are locked down and controlled. If your goal is to craft unique outputs suitable to unique circumstances, industrial process is your enemy.

Where then are the management leverage points if industrial process is not the answer? McDonalds is not the only way to run restaurant. In a knowledge work environment, both design and management responsibilities must be more widely distributed and shared. Peter Drucker captured this when he observed that the first question every knowledge worker must ask is “what is the task?â€

Answering that question entails understanding the materials and tools available. From there, knowledge workers can design approaches to creating the necessary unique knowledge artifacts. Habits, routines, rituals, and practices replace rigid processes. In a fine restaurant, the day’s fresh ingredients set the menu and the menu guides which preparation and cooking techniques will be called for that evening. Line cooks, sous chefs, and chefs collaborate to create the evening’s dining experience.

The building blocks for constructing suitably unique final products are learned over years of practice and experimentation. They are passed on through observation and apprenticeship. In a volatile knowledge economy, they must also be subject to constant evolution, refinement, and innovation.

Learning as a craft practice

In the pre-industrial craft world, learning could be a simple process. Find a master and apprentice yourself to them. Time would suffice to transfer expertise and skill from master to apprentice.

We do not live in that world.

In an industrial world, learning was focused on fitting people to the work. Open-ended apprenticeship was replaced with narrow training programs to learn the specifics of where humans fit into a larger, engineered, process design.

We do not live in that world.

Integrating a craft point of view with the pace of the technological environment that now exists makes learning a craft practice to master.

We are all permanent apprentices. We are also all permanent masters of our craft. Apprenticeship must become conscious and designed. Mastery will always be temporary. Our understanding of materials, tools, and practices will always be dynamic. Learning and performing will be in constant tension.

I’m fundamentally lazy so I’m always looking for tools to simplify whatever task I’m trying to accomplish. I’m currently teaching a course in project management and we’re working through how to build good project plans. In project management circles, there seems to be an infinite set of options for software tools to support project execution. Tool support for earlier stages receives less attention.

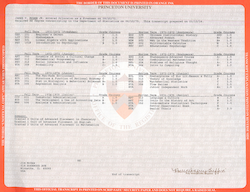

I’m fundamentally lazy so I’m always looking for tools to simplify whatever task I’m trying to accomplish. I’m currently teaching a course in project management and we’re working through how to build good project plans. In project management circles, there seems to be an infinite set of options for software tools to support project execution. Tool support for earlier stages receives less attention. The Fall term is settling into its rhythm. I’ve shared my usual story of my own academic transcripts containing at least one of every possible letter grade. I was a natural, but undisciplined, student. I paid attention to meeting prerequisites for subsequent courses and meeting the requirements of my major but I didn’t think about the practicalities of how what I was learning flowed from one course to the next. More broadly, I gave little thought to the connections between what I was studying now and what I would need to know later for any value of later beyond the final.

The Fall term is settling into its rhythm. I’ve shared my usual story of my own academic transcripts containing at least one of every possible letter grade. I was a natural, but undisciplined, student. I paid attention to meeting prerequisites for subsequent courses and meeting the requirements of my major but I didn’t think about the practicalities of how what I was learning flowed from one course to the next. More broadly, I gave little thought to the connections between what I was studying now and what I would need to know later for any value of later beyond the final. I’ve long been a fan of

I’ve long been a fan of  I started this blog in the earlyish days of blogging. I was teaching a course at Northwestern’s Kellogg School about strategic uses of information technology. The blog offered a way to share thoughts with my students. I quickly plugged into a community of like-minded bloggers in education and in knowledge work in general. In time, that network connected me to

I started this blog in the earlyish days of blogging. I was teaching a course at Northwestern’s Kellogg School about strategic uses of information technology. The blog offered a way to share thoughts with my students. I quickly plugged into a community of like-minded bloggers in education and in knowledge work in general. In time, that network connected me to

Application and software vendors are offering more customer support in places like Facebook in addition to their more formal channels. Done well, this enlists volunteer help from users, recreating some of the feel from the earlier days of the online world where there was often a strong sense of shared community.

Application and software vendors are offering more customer support in places like Facebook in addition to their more formal channels. Done well, this enlists volunteer help from users, recreating some of the feel from the earlier days of the online world where there was often a strong sense of shared community. Back in April I started to play with the

Back in April I started to play with the  It was essentially a casting call. I was interviewing retired and semi-retired executives to fill a role in a training simulation we were building. We needed someone to play the part of the client CEO and someone had introduced me to Scott. Scott was a central casting silver fox, tanned from a recent visit to Florida.

It was essentially a casting call. I was interviewing retired and semi-retired executives to fill a role in a training simulation we were building. We needed someone to play the part of the client CEO and someone had introduced me to Scott. Scott was a central casting silver fox, tanned from a recent visit to Florida. “It’s always best to start at the beginning.â€

“It’s always best to start at the beginning.â€ I’ve been

I’ve been