I’ve been writing at a keyboard now for five decades. As it’s Mother’s Day, it is fitting that my mother was the one who encouraged me to learn to type. Early in that process, I was also encouraged to learn to think at the keyboard and skip the handwritten drafts. That was made easier by my inability to read my own handwriting after a few hours.

I’ve been writing at a keyboard now for five decades. As it’s Mother’s Day, it is fitting that my mother was the one who encouraged me to learn to type. Early in that process, I was also encouraged to learn to think at the keyboard and skip the handwritten drafts. That was made easier by my inability to read my own handwriting after a few hours.

I first started text editing as a programmer writing Fortran on a Xerox SDS Sigma computer. I started writing consulting reports on Wang Word Processors. When PCs hit the market, I made my way through a variety of word processors including WordStar, WordPerfect, and Microsoft Word. I also experimented with an eclectic mix of other writing tools such as ThinkTank, More, Grandview, Ecco Pro, OmniOutliner, and MindManager. Today, I do the bulk of my long-form writing using Scrivener on a Mac together with a suite of other tools.

The point is not that I am a sucker for bright, shiny, objects—I am—or that I am still in search of the “one, true tool.” This parade of tools over years and multiple technology platforms leads me to the observation that we would be wise to spend much more attention to our mental models of software and the thinking processes they support.

That’s a problem because we are much more comfortable with the concrete than the abstract. You pick up a shovel or a hammer and what you can do is pretty clear. Sit down at a typewriter with a stack of paper and, again, you can muddle through on your own. Replace the typewriter and paper with a keyboard and a blank screen and life grows more complicated.

Fortunately, we are clever apes and as good disciples of Yogi Berra we “can observe a lot just by watching.” The field of user interface design exists to smooth the path to making our abstract tools concrete enough to learn.

UI design falls short, however, by focusing principally at the point where our senses—sight, sound, and touch—meet the surface of our abstract software tools. It’s as if we taught people how to read words and sentences but never taught them how to understand and follow arguments. We recognize that a book is a kind of interface between the mind of the author and the mind of the reader. A book’s interface can be done well or done badly, but the ultimate test is whether we find a window into the thoughts and reasoning of another.

We understand that there is something deeper than that words on the page. Our goal is to get behind the words and into the thinking of the author. This same goal exists in software; we need to go behind interface we see on the screen to grasp the programmer’s thinking.

We’ll come back to working with words in a moment. First, let’s look at the spreadsheet. I remember seeing Visicalc for the first time—one year too late to get me through first year Finance. What was visible on the screen mirrored the paper spreadsheets I used to prepare financial analyses and budgets. The things I understood from paper were there on the screen; things that I wished I could do with paper were now easy in software. They were already possible and available by way of much more complex and inscrutable software tools but Visicalc’s interface created a link between my mind and Dan Bricklin’s that opened up the possibilities of the software. I was able to get behind the screen and that gave me new power. That same mental model can also be a hindrance if it ends up limiting your perception of new possibilities.

Word processors also represent an interface between writers and the programmer’s model of how writing works. That model can be more difficult to discern. If writer and programmer have compatible models, the tools can make the process smoother. If the models are at odds, then the writer will struggle and not understand why.

Consider the first stand-alone word processors like the Wang. These were expensive, single function machines. The target market was organizations with separate departments dedicated to the production of documents; insurance policies, user manuals, formal reports, and the like. The users were clerical staff—generally women—whose job was to transform hand written drafts into finished product. The software was built to support that business process and the process was reflected in the design and operation of the software. Functions and features of the software supported revising copy, enforcing formatting standards, and other requirements of a business.

The economics that drove the personal computer revolution changed the potential market for software. While Wang targeted organizations and word processing as an organizational function, software programmers could now target individual writers. This led to a proliferation of word processing tools in the 1980s and 1990s reflecting multiple models of the writing process. For example, should the process of creating a draft be separate from the process of laying out the text on the page? Should the instructions for laying out the text be embedded in the text of the document or stored separately? Is a long-form product such as a book a single computer file, a collection of multiple file, or something else?

Those decisions influence the writer’s process. If your process meshes with the programmer’s, then life is good. If they clash, the tool will get in the way of good work.

If you don’t recognize the issue, then your success or failure with a specific tool can feel capricious. If you select a tool without thinking about this fit, then you might blame yourself for problems and limitations that are caused by using a tool that clashes with your process.

Suppose we recognize that this issue of mental models exists. How do we take advantage of that perspective to become more effective in leveraging available tools? A starting point is to reflect on your existing work practices and look for the models you may be using. Are there patterns in the way you approach the work? Do you start a writing project by collecting a group of interesting examples? Do you develop an explicit hypothesis and search out matching evidence? Do you dive into a period of research into what others have written and look for holes?

Can you draw a picture of your process? Identify the assumptions driving your process? Map your software tools against your process?

These are the kinds of questions that designers ask and answer about organizational processes. When we work inside organizations, we accept the processes as a given. In today’s environment for knowledge work, we have the capacity to operate effectively at a level that can match what organizations managed not that long ago. Given that level of potential productivity and effectiveness, we now need to apply the same level of explicit thought and design to our personal work practices.

We are imitative creatures. We are happier copying someone else’s approach than inventing solutions based on the actual problem at hand. How often do you encounter situations where change is called for and the first response to any suggestion is “where has this been done before?” For all the talk of innovation, I often wonder how anything new ever happens.

We are imitative creatures. We are happier copying someone else’s approach than inventing solutions based on the actual problem at hand. How often do you encounter situations where change is called for and the first response to any suggestion is “where has this been done before?” For all the talk of innovation, I often wonder how anything new ever happens.

I’ve carried a pocket knife since my days as a stage manager/techie in college. A handful of useful tools in hand beats the perfect tool back in the shop or office. Courtesy of the TSA I have to remember to leave it behind when I fly or surrender it to the gods of security theater but every other day it’s in my pocket. There is, in fact, an entire subculture devoted to discussions of what constitutes an

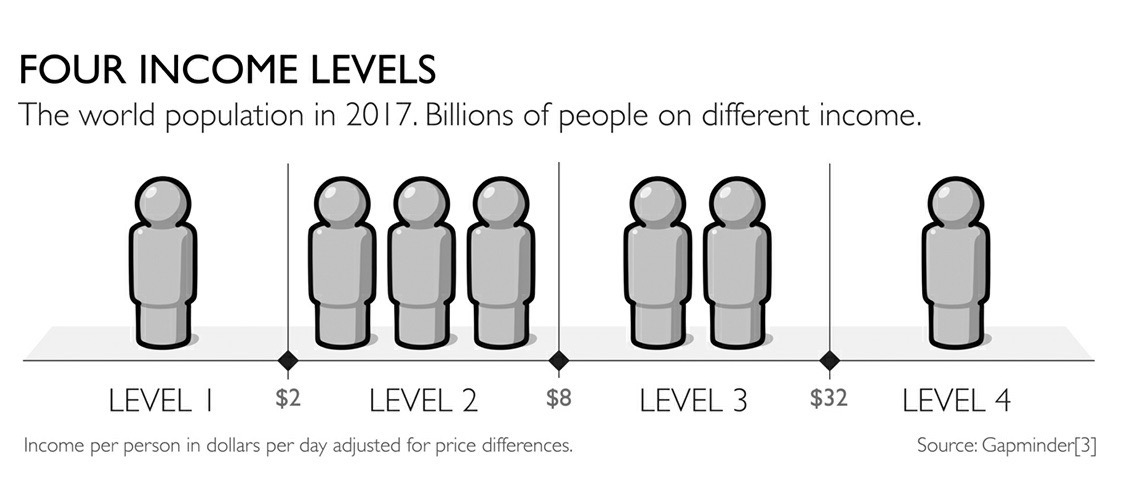

I’ve carried a pocket knife since my days as a stage manager/techie in college. A handful of useful tools in hand beats the perfect tool back in the shop or office. Courtesy of the TSA I have to remember to leave it behind when I fly or surrender it to the gods of security theater but every other day it’s in my pocket. There is, in fact, an entire subculture devoted to discussions of what constitutes an  “Trust but verify” is no longer an effective strategy in an information saturated world. When Ronald Reagan quoted the Russian proverb in 1985, it seemed clever enough; today it sounds hopelessly naive. If we are reasonably diligent executives or citizens, we understand and seek to avoid confirmation bias when important decisions are at hand. What can we do to compensate for the forces working against us?

“Trust but verify” is no longer an effective strategy in an information saturated world. When Ronald Reagan quoted the Russian proverb in 1985, it seemed clever enough; today it sounds hopelessly naive. If we are reasonably diligent executives or citizens, we understand and seek to avoid confirmation bias when important decisions are at hand. What can we do to compensate for the forces working against us?

I’ve been writing at a keyboard now for five decades. As it’s Mother’s Day, it is fitting that my mother was the one who encouraged me to learn to type. Early in that process, I was also encouraged to learn to think at the keyboard and skip the handwritten drafts. That was made easier by my inability to read my own handwriting after a few hours.

I’ve been writing at a keyboard now for five decades. As it’s Mother’s Day, it is fitting that my mother was the one who encouraged me to learn to type. Early in that process, I was also encouraged to learn to think at the keyboard and skip the handwritten drafts. That was made easier by my inability to read my own handwriting after a few hours. I’m gearing up to teach project management again over the summer. There’s a notion lurking in the back of my mind that warrants development.

I’m gearing up to teach project management again over the summer. There’s a notion lurking in the back of my mind that warrants development.

Our admiration for the assembly line is so deep that we are suckers for the promise of “proven systems” regardless of their feasibility. We so treasure predictability and control that the promise seduces no matter how many times it is broken.

Our admiration for the assembly line is so deep that we are suckers for the promise of “proven systems” regardless of their feasibility. We so treasure predictability and control that the promise seduces no matter how many times it is broken.