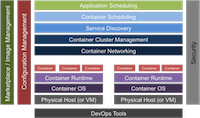

Last time out we talked about the idea of a stack as a simple metaphor for organizing and thinking about underlying complexity in technology or organizations. I thought it would be worth taking a look at some of the origins of fighting complexity in the technology realm that brought us here.

Last time out we talked about the idea of a stack as a simple metaphor for organizing and thinking about underlying complexity in technology or organizations. I thought it would be worth taking a look at some of the origins of fighting complexity in the technology realm that brought us here.

Computer software is among the most complex constructs of human creativity. Wrestling that complexity under control has occupied the attention of many smart people. Talking about technology stacks is a shorthand way of thinking about this complexity. We’ve touched on the problem of complexity. The other problem we have to address is change.

There are three core concepts from the systems design world that are worth understanding and adapting to the organizational realm. They all relate to the design question of how best to carve things up into reasonably discrete pieces. The world of software is all thought stuff. There are few external constraints to shape your designs.

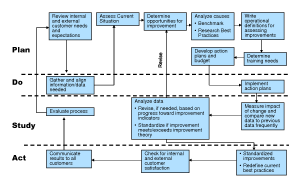

Systems designers look at three concepts when they are evaluating design choices about ways to carve a big system into more manageable pieces:

- information hiding

- coupling

- cohesion

Information hiding is the systems design equivalent of “need to know.†How do you keep what you reveal about a module to a minimum? Put another way, what secrets are useful to keep.

Coupling and cohesion are complementary concepts. Cohesion is a measure of how closely the internal details of a module fit together. Do we have a team where everyone knows their role and responsibilities or do we have a random collection of people moving in the same general direction.

Coupling measures the degree of connectivity between modules. Cars traveling the same highway are more loosely coupled than the cars making up a commuter train.

If you’re interested in digging deeper, I’ve added pointers to some of the underlying literature where these notions were worked out. Think of it as a bit of information hiding on my part. If you’re comfortable with this level of explanation, you’re done. If not, you have the path to where to go next.

Once you have a clean mental model of a stack of modules formed by applying notions of information hiding, coupling, and cohesion you have a strategy to cope with complexity with less risk of finding yourself overwhelmed. If you can get a reasonable answer to your question at the layer you see, then you’re done. If not, you work your way down to the next layer. There are few questions that will require you to dig through multiple layers to find an answer. There are fewer still that require you to keep every layer in the stack in mind to understand.

Next time we’ll see how we might translate this strategy from technology to organizations.

Pointers to background work.

Nygren, Natalie. n.d. “Missing in Action: Information Hiding.†Steve McConnell. Accessed March 7, 2020. .

Parnas, D L. 1972. “On the Criteria To Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules.†Communications of the ACM 15 (12): 6.

Stevens, W P, G J Myers, and L L Constantine. 1974. “Structured Design.†IBM Systems Journal 13 (2).

I’m a fan of case studies–both as a teaching tool and a research tool. They’re often disparaged. And caricatured. I certainly had my own reservations when I first encountered them. Why couldn’t somebody just lay out the problem and get on with solving it? What was the point of all the arguments and background and history and politics?

I’m a fan of case studies–both as a teaching tool and a research tool. They’re often disparaged. And caricatured. I certainly had my own reservations when I first encountered them. Why couldn’t somebody just lay out the problem and get on with solving it? What was the point of all the arguments and background and history and politics? After church yesterday, I had a quick conversation with a relatively new parishioner. I had learned that Ben was from St. Louis, as was I. This was a perfect opening to ask the first question that always gets posed whenever two St. Louisans meet: “Where did you go to school?â€

After church yesterday, I had a quick conversation with a relatively new parishioner. I had learned that Ben was from St. Louis, as was I. This was a perfect opening to ask the first question that always gets posed whenever two St. Louisans meet: “Where did you go to school?â€ “But, you’re not an asshole!?â€

“But, you’re not an asshole!?â€ There’s a story of the two watchmakers that Herbert Simon tells in

There’s a story of the two watchmakers that Herbert Simon tells in  There’s been a recent cluster of articles on the productivity benefits realized from capping

There’s been a recent cluster of articles on the productivity benefits realized from capping