I’ve been on a quest over the past year or so to understand the importance of getting outside of your head if you want to be more effective as a knowledge worker. The inciting incident for this quest was reading How to Take Smart Notes by Sonke Ahrens (my review is at Unexpected Aha Moments – Review – How to Take Smart Notes). I think I’m past the “refusal of the call” but I don’t know that there is a mentor to be found, although there do seem to be many others walking similar paths. Ahrens tells a story about Nobel physicist Richard Feynman that I traced back to James Gleick’s biography of Feynman (Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman). Gleick tells it this way:

I’ve been on a quest over the past year or so to understand the importance of getting outside of your head if you want to be more effective as a knowledge worker. The inciting incident for this quest was reading How to Take Smart Notes by Sonke Ahrens (my review is at Unexpected Aha Moments – Review – How to Take Smart Notes). I think I’m past the “refusal of the call” but I don’t know that there is a mentor to be found, although there do seem to be many others walking similar paths. Ahrens tells a story about Nobel physicist Richard Feynman that I traced back to James Gleick’s biography of Feynman (Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman). Gleick tells it this way:

[Feynman] began dating his scientific notes as he worked, something he had never done before. Weiner once remarked casually that his new parton [In particle physics, the parton model is a model of hadrons] notes represented “a record of the day-to-day work,†and Feynman reacted sharply. “I actually did the work on the paper,†he said. “Well,†Weiner said, “the work was done in your head, but the record of it is still here.†“No, it’s not a record, not really. It’s working. You have to work on paper, and this is the paper. Okay?â€

This is what my math teachers would label a “non-trivial” insight. However, if they made that point when I was studying math, it sailed right past me. Sure, you could sometimes salvage credit on a problem set by “showing your work” but it never occurred to me that “showing” and “doing” your work was the same thing. I always felt that the work was supposed to be going on inside my head, that the goal was to get everything inside my head before exam time rolled around. Certainly the testing and evaluation systems reinforced the notion that you were supposed to keep the important stuff in your head; storing it elsewhere was likely to land you in serious trouble if you got caught referring to that external storage during the exam.

Some of this is the problem of “toy problems.” In teaching settings, you need to work with problems that can fit into class sessions and semester-long projects. With most of these you can get away with lazy practices; you can manage it all in your head. If you’re lucky, the course designer may try to force you to follow good practices above and beyond simply finding the “right answer.” As a student, you’re still likely to miss the point of learning the supporting practices. [As an aside, this is now something I’m working on improving in my course design and delivery]

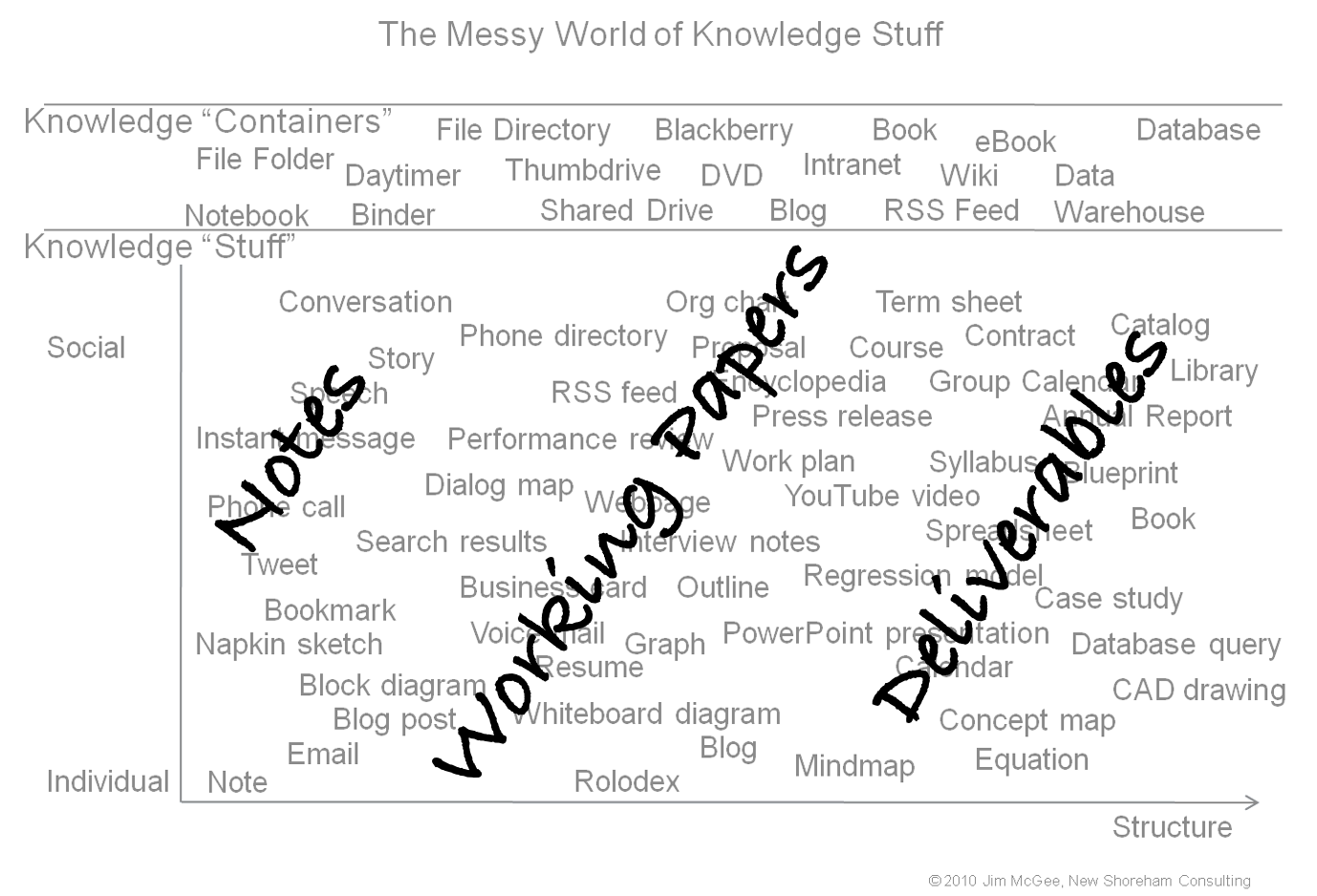

Once you start to look for it, you do see that smart people have been offering good advice about how to deal with the limitations of your unaided memory and brain. Think of Anne Lamott’s advice to write “shitty first drafts,” Peter Elbow’s practice of “freewriting,” Tony Buzan’s advocacy of “mind mapping,” or John McPhee’s ruminations on “Structure.” All of these are the kinds of techniques and practices that can make us more effective at creating quality knowledge work artifacts. But it isn’t clear that we encounter this advice as early or effectively as we should.

If we do stumble across this category of advice and fold it into our work practice, we can gain a meaningful edge. We’ve taken elements of the work out of our heads and into our extended work environment. We’ve increased the range and complexity of material we can now draw on to create better deliverables.

I’m in the midst of working this out for myself. I actually think that this is something that each knowledge worker is going to have to design for themself. I’m suspicious of claims that someone’s new tool or application contains the secret answer. Right now, I’m investigating various sources with an eye toward identifying design principles and ideas worth extracting or reverse engineering.

Some of the more interesting trains of thought include:

- §Taking knowledge work seriously (Stripe convergence talk, 2019-12-12) | Evergreen note-writing helps insight accumulate | Executable strategy for writing

- Â Tool for Thought – The New York Times

- Â stevenberlinjohnson.com: Tool For Thought

- Â The Incredible Creative Power of the Index Card – Forge

- Â Here (with 2 Years of Exhausting Photographic Detail) Is How To Write A Book

- Â Why Roam is Cool – Divinations

- Â Getting compound interest on your thoughts with Conor White-Sullivan

- Â The One Thing You Need to Learn to Fight Information Overload

- Â Berners-Lee: Talk at Bush Symposium: Notes

-  This is how I did it: created the best reference manager set up for research & writing – Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory at Colorado State University

-  Drawing Diagrams in the Head and with Technology: Benefits, Cognitive Mechanisms, Artificial Intelligence, Apps, and Sleep Onset Dreaming – CogZest

-  Create a Zettelkasten for your Notes to Improve Thinking and Writing • Zettelkasten Method

-  How to Write a Note That You Will Actually Understand • Zettelkasten Method

- Building a Second Brain: An Overview – Forte Labs

The late Peter Drucker continues to be a source of insight and inspiration for me.

The late Peter Drucker continues to be a source of insight and inspiration for me.

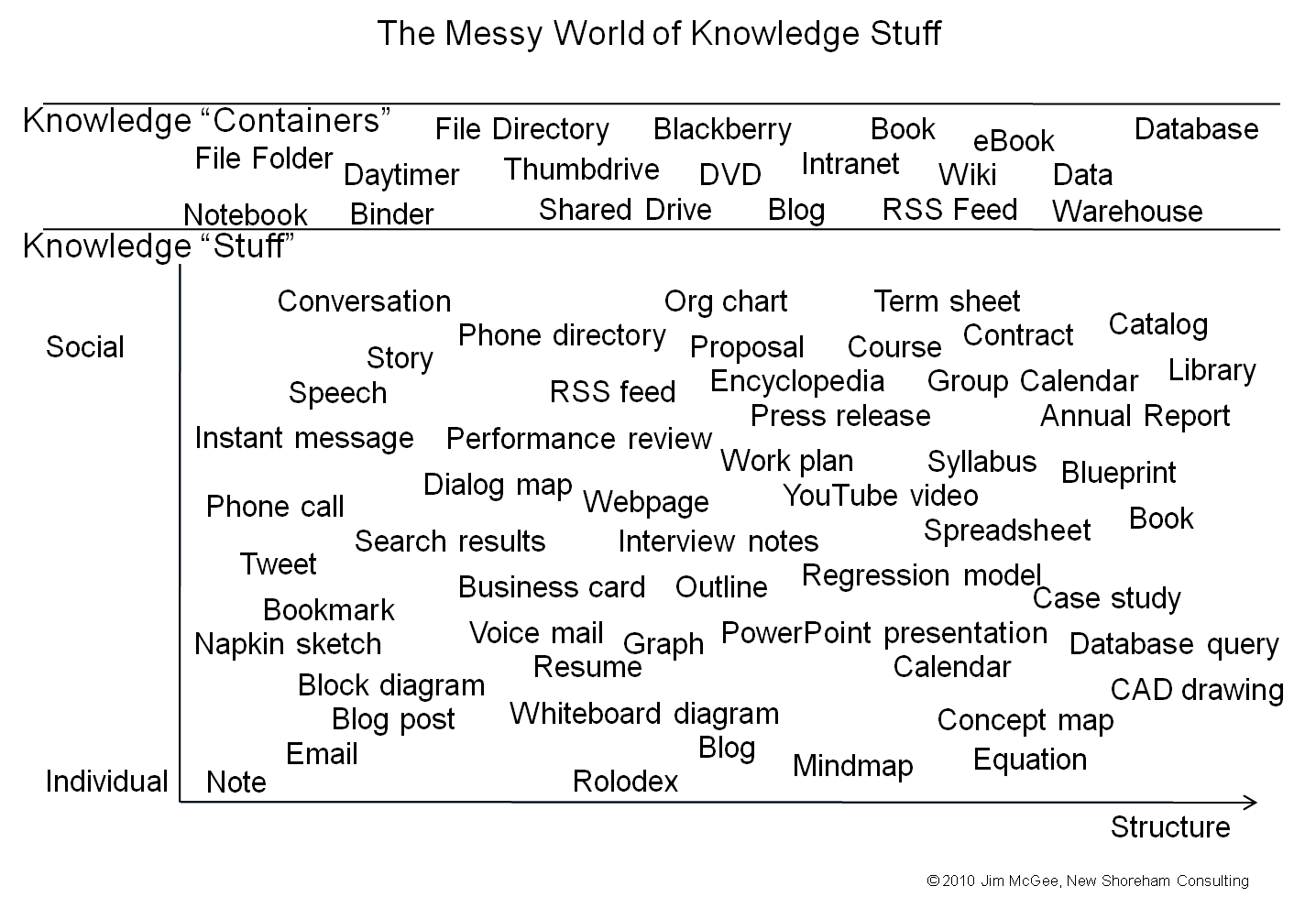

Back when I was a Chief Knowledge Officer, I struggled with the problems of how to better tap the collective knowledge and experience of an organization filled with extraordinarily smart people. There were the technical problems of what to collect and how to organize it. There were the organizational change problems of how to persuade those same smart people that sharing their expertise my way was in their best interest.

Back when I was a Chief Knowledge Officer, I struggled with the problems of how to better tap the collective knowledge and experience of an organization filled with extraordinarily smart people. There were the technical problems of what to collect and how to organize it. There were the organizational change problems of how to persuade those same smart people that sharing their expertise my way was in their best interest.

Early in my education as a computer programmer I encountered Niklaus Wirth’s seminal Algorithms + Data Structures = Programs. The fundamental insight was that algorithms and data structures have to be fashioned in concert; a good choice of data structure can simplify an algorithm, a clever algorithm might allow a simple data structure.

Early in my education as a computer programmer I encountered Niklaus Wirth’s seminal Algorithms + Data Structures = Programs. The fundamental insight was that algorithms and data structures have to be fashioned in concert; a good choice of data structure can simplify an algorithm, a clever algorithm might allow a simple data structure. Working from home is revealing how much of our daily work is kept in check by guardrails we don’t see or think about. We’re struggling to explicitly handle and deal with stuff that the environment handled for us invisibly. I’ve written elsewhere about the value of

Working from home is revealing how much of our daily work is kept in check by guardrails we don’t see or think about. We’re struggling to explicitly handle and deal with stuff that the environment handled for us invisibly. I’ve written elsewhere about the value of