I stumbled across an interesting opinion piece in the Washington Post recently; want kids to learn math? Level with them that it’s hard. Learning to do knowledge work, like learning to do math, takes disciplined work. Tiago Forte is one of the people putting in the necessary work and sharing what he’s learning with the rest of us. In this piece, Forte turns to the kitchen and the realm of professional chefs for insight. Particularly, their obsession with order and preparation; mise-en-place.

I stumbled across an interesting opinion piece in the Washington Post recently; want kids to learn math? Level with them that it’s hard. Learning to do knowledge work, like learning to do math, takes disciplined work. Tiago Forte is one of the people putting in the necessary work and sharing what he’s learning with the rest of us. In this piece, Forte turns to the kitchen and the realm of professional chefs for insight. Particularly, their obsession with order and preparation; mise-en-place.

Knowledge work lessons from the kitchen

Forte explores the following mise-en-place practices for relevant parallels to knowledge work

1. Sequence

2. Placeholders

3. Immersive vs. process time

4. Finishing mindset

5. Small, precise movements

6. Arrangement

“Sequencing,” for example, looks at how decisions about the layout of tools and ingredients aids or hinders the flow of execution. You don’t want to be rummaging around for a whisk when you need one. Thinking through the process before executing will surface opportunities to sequence work to your advantage.

Forte’s riff on “immersive vs. process time” may be the most interesting. Forte maps immersive time to Cal Newport’s deep work distinction. Process time on the other hand encompasses settings with a time component that runs independently of your attention and focus. In cooking, process time might be the 15 minutes it will take for rice to cook regardless of when you start the process. It may only take a minute of your attention to launch that cooking process but you want to take that minute of focus when it will do the most good. Start the rice now and it will be ready when you need it later. Wait, and you delay the entire process while you watch the rice cook.

There are times when the back burner is the right place for the rice to be cooking while you pay attention to something more important. In knowledge work, the example that springs to mind is Stephen King’s advice to stick a freshly finished manuscript in a drawer for six weeks while you attend to something else. Doing that is taking advantage of your subconscious mind’s capacity to work on creative tasks without your input or attention.

A sticky sequencing problem

Forte has been developing and sharing his system for managing knowledge work for several years now. His Building a Second Brain training course is highly regarded. Although I haven’t sprung for the course, I do pay for access to his other materials and have read his books. I’m picking on Forte here in much the same way that Alan Kay once described the Mac as the “first personal computer worth criticizing.” Whatever it’s flaws, his analysis sparks responses that move the entire argument forward.

There’s a bit of a sequencing problem in his own analysis, here, because he’s invested so much time in his own systems. His analysis of mise-en-place is unavoidably influenced by the design decisions he’s already made and internalized.

Here’s an example of where Forte’s current thinking distorts his analysis of mise-en-place. Talking about the role of sequencing tasks, Forte asserts;

Once we realize the importance of sequence, it becomes apparent that not all moments are created equal: the first tasks matter much more than the later ones.

I will grant the first part of his claim; all moments are not equal. It does not follow, however, that “first tasks matter much more than the later ones.” Forte wants to make a point about the importance of first tasks; that’s pretty conventional wisdom in multiple traditions and settings. But I think it is a hill too far to make a blanket assertion that first tasks always matter more than later ones. In fact, Forte contradicts his own point a bit later when he talks of the importance of a “finishing mindset.”

You encounter ideas in the order you encounter them. The best you can hope for is to be cognizant of that and temper your assessments and enthusiasms for related ideas as you discover them.

A more troubling flaw in the argument

There is a lot to like in Forte’s exploration of mise-en-place. There’s a critical step in his argument, however, that I object to. Forte turns to the world of professional chefs because

It’s time that we had a working system for the mass production of high-quality knowledge work

“Mass production of high-quality knowledge work” is a nonsensical proposition. As a diner in a restaurant, my serving of Coquilles St. Jacques Provencale had better well be identical in all important respects with my dinner companion’s. But don’t try to hand me the marketing strategy you just prepared for my chief rival. Balancing Uniqueness and Uniformity in Knowledge Work has to drive the design of knowledge work practices and methods.

There are things to be learned about doing better knowledge work from contemplating mise-en-place. Knowledge work that makes an impact is more about inventing new recipes than about being more efficient and productive in churning out known recipes for tonight’s diners. You do want a solid mise-en-place set up before you embark on experimenting with recipes. You want your environment set up and tuned so that you can focus your attention and creativity on inventing some new and wonderful delectable. But if the lunch rush is at the door, you’re not doing knowledge work, you’re doing production work. And you need to be clear about the difference.

In the early weeks and months of getting Diamond off the ground, we were intentional about the kind of organizational culture we wanted to create. Within the founding group we had decades of cumulative experience, mostly in organizations known for the strength of their culture together with a sprinkling of less pleasant experiences.

In the early weeks and months of getting Diamond off the ground, we were intentional about the kind of organizational culture we wanted to create. Within the founding group we had decades of cumulative experience, mostly in organizations known for the strength of their culture together with a sprinkling of less pleasant experiences. One of my bad habits is obsessing about my deficiency of good habits. I know that good habits are important because the nuns and monks were relentless in telling me so; decades later their ambivalence about my academic success without suitable discipline still lingers.

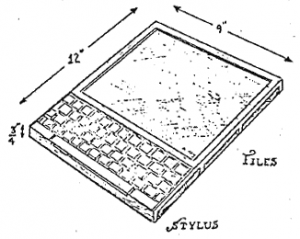

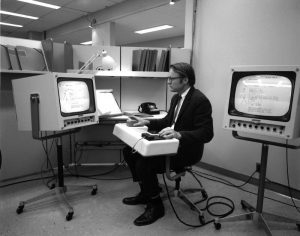

One of my bad habits is obsessing about my deficiency of good habits. I know that good habits are important because the nuns and monks were relentless in telling me so; decades later their ambivalence about my academic success without suitable discipline still lingers. The notion of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) is experiencing something of a renaissance. This rebirth is being driven by a combination of new apps, new ideas, and new thinkers promoting their wares. The apps, ideas, and thinkers are all worth paying attention to. At the same time. the brightness of shiny new things is obscuring important history and context.

The notion of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) is experiencing something of a renaissance. This rebirth is being driven by a combination of new apps, new ideas, and new thinkers promoting their wares. The apps, ideas, and thinkers are all worth paying attention to. At the same time. the brightness of shiny new things is obscuring important history and context. When I was first learning to be a project manager one of the mantras drummed into me was “plan the work, work the plan.” Hidden in this advice was a distinction between planning and doing. Today, we are immersed in doing; managing has been pushed to the margins. “Plan the work, work the plan” has shrunk to “work, work.”

When I was first learning to be a project manager one of the mantras drummed into me was “plan the work, work the plan.” Hidden in this advice was a distinction between planning and doing. Today, we are immersed in doing; managing has been pushed to the margins. “Plan the work, work the plan” has shrunk to “work, work.” In April, 2003, the late

In April, 2003, the late