The best way to have a good idea is to have lots of ideas

Linus Pauling

I suppose it’s fitting that I have struggled with this blog post far more than most. It began with a desire to improve the rhythm and cadence of completing and published writing deliverables. Having just passed nineteen years writing this blog, you would think I was beyond fits of teenage angst. Maybe the onset of blogging adulthood is more daunting than I realized.Â

I’ve always liked the Pauling quote. Having lots of ideas has never been a particular problem for me, so I’ve trusted that some reasonable portion of them would be good enough to share. For a long time, I attributed my occasional struggles to focus on a particular train of thought on my ADD. Bright shiny objects always promise a dopamine hit, but I’ve felt like I’ve been able to keep it enough under control.Â

It occurs to me, however, that my ADD simply serves as an early introduction into a world that we all now live in. We all swim in an overwhelming abundance of ideas. Our training and practice focuses on turning individual ideas into a desired deliverable, whether that is a blog post, a client presentation, or a spreadsheet analysis for our boss.Â

While there’s much to be learned about that idea to deliverable evolution, there’s another layer of knowledge work practice that we must tackle. That thread of idea to deliverable is one element of a collection of threads and you have to manage the collection as something distinct from any one thread.Â

Simply splitting the problem into two layers is a step forward for me. I have a reasonable handle on the first layer; I know how to take an idea, develop it, extend it, and polish it into a deliverable. As a creative task, however, that process is rarely linear. Ideas are not widgets, you can’t simply plow ahead from idea to deliverable. You often need to set things aside and let them cook.Â

Which is where the second layer comes into play. What do you pick up when you set the first idea aside? Presumably another idea that you set aside earlier or a new idea trying to seduce you. You now have a management problem as well as a creation problem.Â

The management problem is about selecting ideas, monitoring progress, switching, sequencing, timing, and cadence. This is operating at a different level of abstraction from the creation process.Â

At small scales, you can likely manage organically. There aren’t so many threads that you can’t keep most or all of the management issues in your head. With time and the accumulation of a body of work, it’s worthwhile to externalize the management problem and not try to rely on the limits of memory. At the same time, the management process must be subordinate to the creative process.Â

Over the past eighteen months or so, I’ve been gradually retooling my baseline creative practices around a more disciplined note-centered practice. Like any retooling, this has led to a temporary drop in output. As committed to improvement as I may be, there’s still muscle memory to be overcome. Even bad habits are still habits that require extra energy to break down and replace. Some markers of this journey that have risen to things worth sharing include:

Early on, what management of the process I did was on the proverbial back of an envelope. Keep a list of ideas as they came to me and pick something off the list when I sat down to write the next piece. Look back at the last few blog posts and write a follow up piece. Do this for any length of time, however, and the envelope gets pretty full

My next thought was to take the list off the back of the envelope and formalize it. I dug into the approaches of other writers who’ve gone through this evolution. Among the appealing approaches I ran into were:

These approaches, however, don’t scale well. As your body of work grows, you risk spending more time maintaining the management control system than you do creating new work. That misses the point entirely.Â

Some Zettelkasten advocates claim that the necessary tools and structure emerge as you gain more experience and grow your collection of notes:

This hasn’t played out for me. Setting aside the hypothesis that this simply reflects my personal limitations, what’s missing?Â

This comes back to the distinction between creating and managing. Most of the discussion and advice I’ve been able to review is focused almost exclusively on creation. It either ignores managing the process as a whole or presumes that what needs to be managed is trivial relative to making creation work more smoothly and reliably.Â

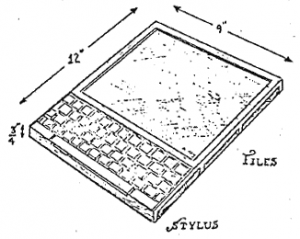

To manage the overall process you need to get above the details of individual work in process (WIP) items. You want to collect just enough data about each item to not have to read the entire piece while you are trying to manage a collection of multiple WIP items. And you need to track the status of each piece of WIP relative to its transition from WIP to final deliverable. Is this item a new idea? A draft? In need of editing? Ready to publish? Published? There’s a life cycle to be defined. This is the metadata you need to make informed decisions about the overall process. Do you have enough WIP to feed your deliverable goals? How does the mix of materials look?

This is a classic data management problem that would seem to call for a simple spreadsheet as DBMS solution. Or a multi-column outline of some sort. Both of those approaches failed relative to the goal of keeping the management system subordinate to the creative system. As I continue the transition to a note-centric creation system, the challenge is to embed the pertinent metadata in the individual notes and create some method of querying the metadata to generate the schedules and lists that will help me manage the creative process. Now that I’ve got a handle on the basic requirements for managing my WIP, the next step is to discover or create the reporting tool.Â

There’s a lot to like about Tiago Forte’s

There’s a lot to like about Tiago Forte’s  The notion of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) is experiencing something of a renaissance. This rebirth is being driven by a combination of new apps, new ideas, and new thinkers promoting their wares. The apps, ideas, and thinkers are all worth paying attention to. At the same time. the brightness of shiny new things is obscuring important history and context.

The notion of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) is experiencing something of a renaissance. This rebirth is being driven by a combination of new apps, new ideas, and new thinkers promoting their wares. The apps, ideas, and thinkers are all worth paying attention to. At the same time. the brightness of shiny new things is obscuring important history and context. I’ve been writing for more than half a century now. One of the early outlets for my writing was the school paper. Most of that was on assignment and there were no bylines on stories. There was, however, one op-ed piece I wrote that did carry a byline. From my cumulative wisdom of 17 years, I opined that our headmaster should come back into the classroom and teach. Scarcely a rabble rousing call to arms but my schoolmates were convinced that I would soon be summoned to Fr. Timothy’s inner sanctum and suitably chastised. That never happened, although we did have a passing chat on the sidelines of a soccer game weeks later where Fr. Timothy agreed with my analysis but suggested I might lack some necessary perspective.

I’ve been writing for more than half a century now. One of the early outlets for my writing was the school paper. Most of that was on assignment and there were no bylines on stories. There was, however, one op-ed piece I wrote that did carry a byline. From my cumulative wisdom of 17 years, I opined that our headmaster should come back into the classroom and teach. Scarcely a rabble rousing call to arms but my schoolmates were convinced that I would soon be summoned to Fr. Timothy’s inner sanctum and suitably chastised. That never happened, although we did have a passing chat on the sidelines of a soccer game weeks later where Fr. Timothy agreed with my analysis but suggested I might lack some necessary perspective. What’s the value of experience in the rapidly changing world we inhabit?

What’s the value of experience in the rapidly changing world we inhabit?