Dehumanizing Knowledge Management. Kim Sbarcea, CKO at Ernst & Young Australia (formerly a knowledge manager at Australian law firms Phillips Fox and Allens Arthur Robinson) dislikes the term knowledge management. It reminds her of “Taylorism”—the scientific management of factory work. Frederick W. Taylor (1856-1915), was a mechanical engineer known for his innovations in industrial engineering. He applied his engineering innovations in a such a way as to de-humanize factory workers to the point of turning them into robots.

Sbarcea likens knowledge management to Taylorism: “KM techniques carry the marks of modernity in that we are trying to ‘manage’ knowledge using command and control language and methodologies. We speak of ‘capturing’ knowledge; we obsess about measuring its effectiveness and watch for the bottom line impact of KM initiatives.” Sbarcea prefers a more “organic” approach to managing knowledge. In fact, she prefers to calls knowledge managers “knowledge enablers.” [excited utterances]

I’m no fan of the term knowledge management (see this post for example) but I think it is a mistake to confound the issue of what to call knowledge management with objections to Taylorism.

Funny about the synchronicity of this coming into my aggregator as I was adding my notes about Peter Drucker’s thoughts on knowledge worker productivity. I’ve been working out some ideas on knowledge work and how to go about improving it. Taylor’s fundamental insights about work are pertinent, as is clarity about what organizational values matter.

Frederick Taylor and work as an improvable process

Praised or vilified, Frederick Taylor is widely acknowledged as one of the seminal thinkers of the industrial age. One of his central contributions was establishing the notion that work was systematically improvable. In the craft world that preceded him, masters set a standard to which apprentices aspired. Moreover, this standard was of the quality of the finished product. Process was essentially invisible; certainly not something worthy of attention.

The knowledge economy brings us back to a world of craft. While Taylor’s methods may not be relevant, his perspective is. His methods are irrelevant because the outputs of knowledge work are one offs. Analyses, decisions, designs, all derive their value from being tailored to the moment and the situation. If it can be reduced to standard operating procedure, it is information work not knowledge work.

This defines knowledge work and knowledge management as a residual problem. Knowledge work is the work that remains after you’ve solved all the easier problems. If you assume that managers are at least intendedly rational (thank you Herb Simon), then they generally tackle problems in the order of least effort/most return. That suggests that as you solve problems, your reward is harder problems left to solve.

There was a time when inventory management was a management responsibility of some import. Over time, operations researchers have structured and defined inventory management problems so that what were managerial decisions become the outputs of accurate information filtered through algorithms. The new managerial problem becomes one of ensuring that the relevant data is accurate and timely.

As a residual problem, the components of what constitutes knowledge work will be a moving target. There are two strategies for dealing with knowledge work in organizations. One is to target the tail of the distribution where problems are on the border between knowledge and information problems. Continue the strategy of turning inventory management into a structured information management process. Leave the remaining problems in the realm of management art.

The second strategy is to attack the center of the distribution. Return to Taylor’s fundamental insight that work is improvable and apply it to the new craft of knowledge work.

Is knowledge work improvable?

Stipulate that improving knowledge work is desirable. That still leaves the question of whether it is feasible. Taylor’s work focused on observing and improving repetitive manual processes. Later efforts extended the success to repetitive information processes. Two underlying strategies underpin much of that success. One strategy is Adam Smith’s basic notion of specialization of steps in processes. The other is a strategy of identifying and eliminating non-value added work steps from the overall process.

How, if at all, do these strategies apply to knowledge work? Does it make sense to think of process improvement at all in the context of knowledge work? Will the strategies of specialization and elimination continue to be the most relevant and productive ones to apply? Or have we reached the limits of return on these approaches and it’s become time to consider alternate strategies?

This is the question that Doug Engelbart identified in the 1960s with his distinction between automation and augmentation. Automation is a substitution strategy. Replace intelligent people in systems with process. It has yielded remarkable results. Augmentation is a partnership strategy. How do you allocate tasks in a system that has both intelligent people and powerful process/technology? In this approach it is worthwhile to think about a general purpose knowledge work process that is relatively simple and very robust.

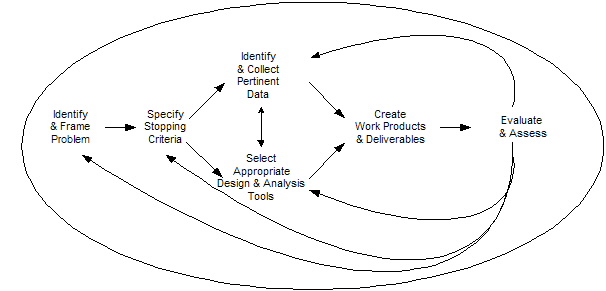

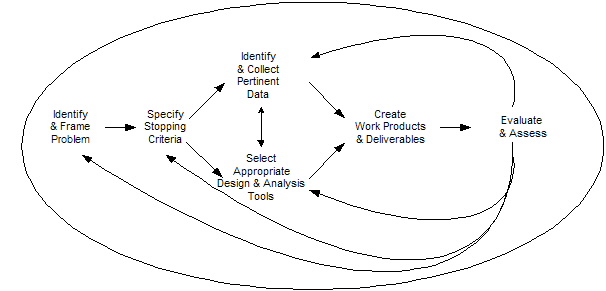

Knowledge Work as a Process

This is a process that is fundamentally iterative. The loops in this process are feedback loops, not opportunities for streamlining. You don’t improve this process by rearranging the steps or breaking them down into specialized tasks to be distributed. Nor are there opportunities to eliminate non-valued added steps. Improving the value of knowledge work calls for different strategies. Two that are worth exploring are to improve the infrastructure at the periphery and to eliminate friction. I’ll come back to that tomorrow or Monday.