I finished my MBA 40 years ago. Courtesy of the current pandemic, I won’t be having the reunion I was looking forward to. But, I have been thinking back to lessons from those days.

I finished my MBA 40 years ago. Courtesy of the current pandemic, I won’t be having the reunion I was looking forward to. But, I have been thinking back to lessons from those days.

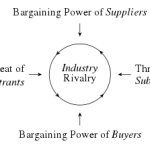

One of the hottest courses my second year was “Industry and Competitive Analysis.” Professor Mike Porter was putting the final touches on what would become Competitive Strategy : Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors and we were the beta testers for what would become the bible of corporate strategy. Because Harvard is committed to the case method, there wasn’t much explicit discussion of theory as theory. You absorbed the theoretical essentials in the course of applying the tools and techniques to the case examples.

Fast forward several years. I’ve left the world of consulting and come back to school one more time. I’m now writing cases instead of reading them. And I’m soaking up formal theory in multiple subjects. One of the courses I take is a course in Industrial Economics from Richard Caves. Industrial Economics is the study of markets and competition from an economist’s perspective. Caves was Porter’s thesis advisor when Porter was getting his Ph.D.

When economists study markets and competition, their driving question is “why do markets fail?” Economists believe in markets and their theories presume perfect competition. Deviations from perfect competition are anomalies to be understood and explained. What gets in the way of the theoretical ideal of Adam Smith where sellers compete on price and features to meet the needs of well-informed buyers. The catalog of things that cause markets to be less than perfectly competitive is long: monopoly power, monopsony power, barriers to entry, barriers to exit, price fixing, collusion, are only a partial list. Economists then seek potential solutions to prevent or eliminate these sources of market failure.

Midway through the course it dawns on me. Porter’s genius in competitive strategy is to recognize that an economist’s market failure is a CEO’s strategic coup. Your goal as a CEO is pick your markets and shape your organization’s behaviors to maximize the probabilities of market failures that work in your favor. I’ve found that to be a very powerful lens for understanding how business strategy plays out in practice.

Following up on

Following up on