We operate in a world of projects, yet few of us are trained in how to think about or manage them. Management education focuses on designing for the routine and predictable. Today’s environment is neither. Projects remain foreign to the bulk of managers in organizations who are accustomed to running ongoing operations. What differentiates success from failure in projects bears little resemblance to what drives success in operations.

Although projects are ubiquitous, project management professionals build their reputations by dealing with the largest and most complex efforts. Lost in this quest to push back the edges of project management is the need to equip mainstream managers in organizations to operate in a project-based world. While expert project managers think about work breakdown structures, scope creep, critical-path mapping, and earned value analysis, the rest of us would like some help learning and understanding the essential 20% of project planning and management that applies to any scale project. How do we become reasonably competent amateur project managers?

The end is where to begin

Until you understand what the end result needs to look like, you have no basis to map the effort it will take to create. Imagine what you need to deliver in reasonable detail, however, and you can work backwards to the sequence of tasks that will bring it into being. How clearly you can visualize the desired end product, in fact, sets your horizon. A clear picture of the end result supports a clear plan of the entire path to that result. A fuzzy picture only allows you to move far enough to generate a sharper picture.

The trick is to visualize the end result as a concrete deliverable that you can hand over. Perhaps it is a slip of paper saying “the answer is 42.” Perhaps it is a working software application, or a marketing strategy. Thinking of it in concrete terms helps in two ways. First, it forces you to be clear about who is to receive this deliverable. If you can’t be clear about who the intended recipient is, you can’t be clear on design, structure, or format of the deliverable. Second, a concrete picture of a deliverable makes it easier to imagine a conversation between you and your audience. The more fully you can imagine that conversation, the easier it will be to imagine the path to creating it. If you can’t visualize a deliverable, you can’t specify the path to create it.

Identifying and connecting the dots

Peter Drucker separates knowledge workers from production workers by noting that the first responsibility of a knowledge worker is to ask “what is the task?” This responsibility flows from the need to define deliverables. In production work, there is no need to define deliverables; they are baked into the design of all repeatable processes. In knowledge work, nothing can happen until a deliverable is specified; understanding the shape of the deliverable binds the shape of the task.

If you think I am being too clever by half, consider the following thought experiment. In a production process, I am quite happy to take whatever output of the process rolls off the line next—one BMW 730i had better be undistinguishable from the next. On the other hand, if I am in the market for a new strategy, I will not accept a copy of the last strategy report McKinsey turned out.

Again, Drucker had things figured out before the rest of us. Knowledge work depends on creating and delivering answers that are unique to the situation at hand (see, for example, Balancing Uniqueness and Uniformity in Knowledge Work).

How do I break down the single task of “produce the necessary unique outcome” into a sequence of manageable tasks that I can string together? How do I specify the dots and how do I thread them together into a path that will get me to my destination? For starters, I had better have some meaningful knowledge of the problem domain. Assuming that knowledge base, there are several heuristics for using that knowledge to specify and sequence appropriate tasks. Keep the following phrases in mind as you take your understanding of the deliverables and the domain and translate that into a possible plan.

- Break things into small chunks (inch pebbles are easier to manage than milestones

- Do first things first

- Ask what comes next

- Group like things together

- Errors and rework are essential to creative work

If you can see how to get from A to B in a single step, you’re likely looking at a potential task. “Small chunks” is a reminder that the only way to eat an elephant is in small bites. Somewhere between a day and a week’s worth of work for an individual is one useful marker of tasks that belong in a project plan. If you can break your deliverables into components, the components may constitute project tasks. Drafting a section of a report or analyzing one element of a budget are the kinds of chunks that make reasonable tasks on a project list.

An initial list of chunks or potential tasks forms the input to the next three heuristics; do first things first, ask what comes next, group like things together. There is a back and forth interaction among these three that is much of the art of good project planning. The art lies in being clever and insightful about sequencing and clustering activities. Suppose the chunk you are considering is “analyze the Midwest sales region.” What happens next? Do we combine that analysis with the outputs from analyzing other sales regions? Do we know how many sales regions exist? Have we included a step to learn how many regions exist? How about a step to get our hands on the pertinent data? Do we have the knowledge and skills to get the data? Is there someone we need to talk to in order to make sense of the incoming data? Is that a big enough question to warrant its own task in the project plan? Raising and answering these questions calls for good mix of domain knowledge and project insight.

All project managers learn that errors and rework are an essential element of creative work. For routine production work, the goal is to eliminate errors and rework. For project work, the goal is to know that they are inevitable and build time and tasks into the plan to deal with them when they occur. Dwight Eisenhower captures the essence of this point in his observation that “plans are useless, planning is everything.” As the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in World War II responsible for planning and leading the D-Day invasion, his words carry weight.

Essential tools

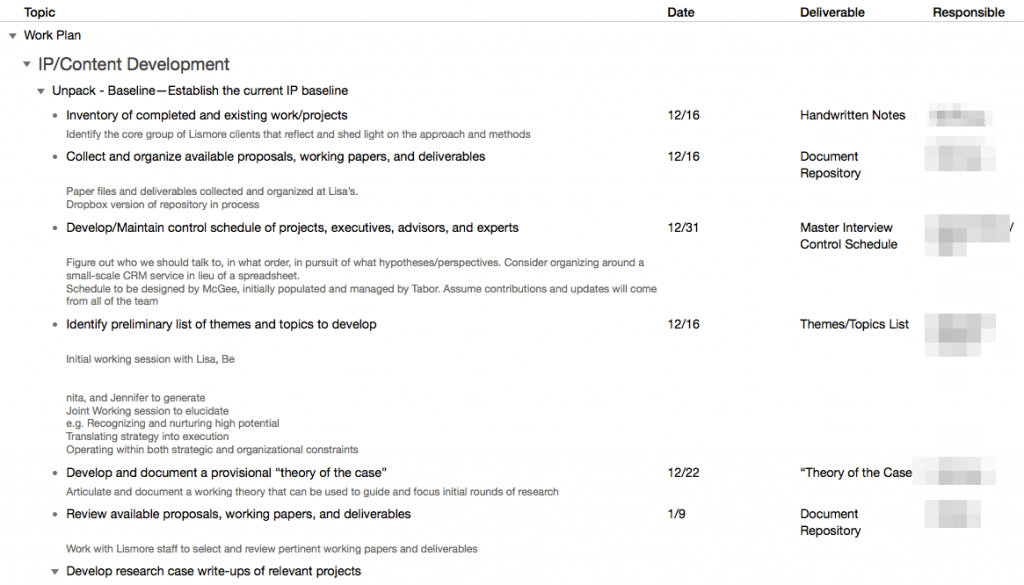

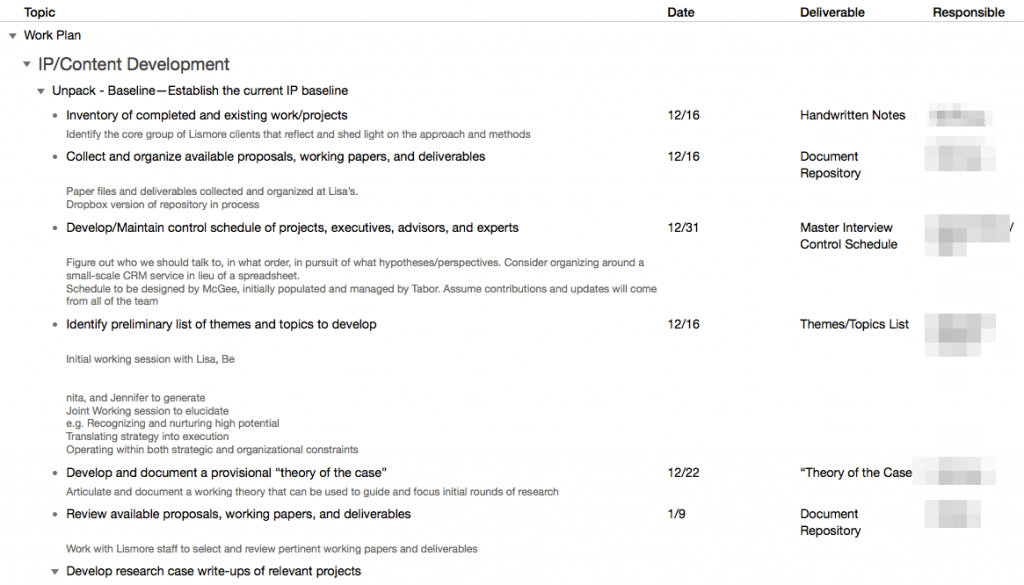

The growing list of chunks can rapidly become overwhelming. There is a substantial industry of vendors and tools promising to bring this complexity under control. As helpful, and possibly necessary, as these tools might be during the execution phase they are more hindrance than help during planning. Two simple tools—a messy outline and a calendar—help better navigate the planning step.

An outline captures the essential need to order and cluster tasks. An outline offers enough structure over a simple todo list to add value without getting lost in the intricacies of a more complex software tool. It helps discover similar tasks, deliverables, or resources that can be grouped together in your plans. It can highlight where preceding or subsequent tasks might be missing. Throughout the iterative process of developing and refining the task outline, a calendar keeps you tuned both to external time constraints and internal deadlines.

There are many good software tools available for working with outlines. If you’re going to be doing project planning on a regular basis—and you will be—it’s well worth adding one to your software toolkit. If you’re so inclined, you might also take advantage of mindmapping software, which typically has an outlining mode. You can use a spreadsheet program in a pinch, but spreadsheets are as well suited to the dynamic demands of thinking through alternate approaches to a project. Here’s an example of a project plan built using an outlining tool. It has everything you need to plan 80% of the projects you will encounter.

At the outset, we’re focused on the value of simply thinking through what needs to be done in what order before leaping to the first task that appears. That’s why an outline is a more useful tool at this point than Microsoft Project or an other full bore project management software. For those projects of sufficient scale and complexity, more powerful tools can be necessary. For most projects, simple tools are all that you will need. For those that ultimately need full-featured project management software, these same simple tools are often a better place to start.

All knowledge work is project work

Drucker’s observation that knowledge work begins with defining the task implies that knowledge work is essentially project work; the economic engine of today and tomorrow. Yet, projects remain foreign to most managers in organizations who are accustomed to running ongoing operations. What separates success from failure in projects bears little resemblance to what drives success in operations.

Why bother increasing project management capabilities at the base instead of the leading edge? All of us must develop a basic level of knowledge and skill in planning and leading projects if we wish to be competent leaders in today’s organizations. Project management is not only a job for professionals. As knowledge workers, we’re all called on to participate in project planning, and often we must lead projects without benefit of formal education in project management.

I’ve been involved with my church’s annual Christmas Pageant for twenty two years. Early on, I helped our youth minister wrangle the hordes of young kids. We lost her to cancer twenty years ago and I was asked to step up and take on the whole show the following year. I now own the production and there is no escape. I get an email each November from our director of youth ministries asking if I will do it again. The request is a polite fiction; there is only one possible answer.

I’ve been involved with my church’s annual Christmas Pageant for twenty two years. Early on, I helped our youth minister wrangle the hordes of young kids. We lost her to cancer twenty years ago and I was asked to step up and take on the whole show the following year. I now own the production and there is no escape. I get an email each November from our director of youth ministries asking if I will do it again. The request is a polite fiction; there is only one possible answer.