Loyola’s Quinlan School has just launched a new Next Generation MBA. Project Management is a required course in the curriculum and I was asked to take the lead in designing that course. We’re now halfway through the first iteration of the course. I had an opportunity this past weekend to speak at PMI Chicagoland’s Career Development Conference and opted to use the course design and rollout effort to reflect on what larger, emerging, lessons I saw.

During the course design process, I learned a new label to describe me. It turns out that I am a “pracademic”; someone who brings a practitioner’s perspective to an academic environment. While it turns out that the label isn’t terribly new, I just stumbled across it.

I assert that if you are a knowledge worker, you need to become a pracademic as well.

What is a pracademic?

A quick glance at Google’s ngram viewer suggests that the term, “Pracademic” traces back to the mid-1970s and saw a significant uptick in the early 2000s. There’s a seminal 2009 academic paper on the term by Paul Posner, “The Pracademic: An Agenda for Reâ€Engaging Practitioners and Academics that’s a good entry point.

The primary focus seems to have been on the notion of bringing relevant practitioner experience back into the academic environment. Like all good portmanteaus, however, pracademic elicits a constellation of reactions.

Among those is the more general notion of blending practical and theoretical knowledge. An admirable and long sought goal but one that, probably unsurprisingly, is more difficult to put into practice than it is to describe in theory.

It’s hard enough to be competent on either side of the divide. Working both sides effectively is harder still. With the continuing and accelerating explosion of knowledge, the need to do precisely that has become simultaneously more challenging and more necessary. This is a topic that has drawn my attention before:

- Taking the half-life of knowledge seriously – McGee’s Musings

- Learning, bodies of knowledge, and half-lives – McGee’s Musings

Living in exponential times means this explosion has always been underway. It’s important to accept that this is an explosion that doesn’t end; there is no point at which the curve is likely to level off. Waiting for things to settle down is a fool’s errand.

If you opt for the role of a pracademic it is a matter of accepting that this is a path you will be walking for as long as you wish or are able. Whatever credentials or experience you might collect, there is no marker for being done.

Why does this matter for knowledge work?

Knowledge work is perhaps the purest expression of this notion. Your capacity to deliver effective results is a function of how well you can assess the practical situations you face and then apply the most pertinent and relevant aspects of your cumulative knowledge base.

While the origins of the term pracademic are anchored in carrying practitioner knowledge back into the academy, knowledge work in the environment we’ve been talking about works the other direction. What does it mean to take theory back into practice?

Knowledge work demands leveraging theory. As a knowledge worker, you are rarely granted the luxury of time off to fully study and integrate the latest and greatest developments in your field of expertise. At the same time, if you don’t continue to add to your expertise, your ability to contribute and make a difference diminishes.

How does this change the shape of practice?

The late Donald Schön of MIT addressed this line of thought with his notion of “reflective practice“. Fundamental to the notion of reflective practice is building and testing a robust theory of action.

My particular interests are in action that occurs in organizational environments; action that calls for coordinating the efforts of multiple actors. Practice takes place within those social and organizational environments. Applying theory within this practice environment benefits from understanding key aspects of how thinking connects to action there.

There is a persistent mythology about organizations that rationality should prevail and that anything other than rational decision making represents some level of pathology. This is an area where academic research and theory is especially illuminating.

There are two aspects of thinking relevant to navigating this environment. The first relates to a distinction between oral and literate thinking. This distinction was mapped out by Walter Ong, a Jesuit historian and philosopher. Ong examined the impact of the invention of writing on culture and institutions. At root, his argument is that literacy enables us to get thinking outside of our heads and that this transition is an essential, prerequisite, step in enabling the rise of rational thought.

While complex rational thought is rooted in literate modes of thinking, organizations are environments that predate literacy. They blend oral and literate modes of thought. Most particularly, organizational power dynamics are rooted in oral modes of thought. Arguments do not carry the day simply by being the most logical and rational. This is puzzling and confusing to those who’ve made the effort to become adept at literate thought.

One rule of literate thought, fortunately, is that you do not simply accept someone else’s word, you go and see for yourself. This leads to the second aspect of accepting the assumption that organizations behave rationally; the discoveries of those who went and looked. There is a growing evidence base about the limits of rationality in organizations.

Herb Simon advanced organizational understanding significantly when he pointed out that our desire for rationality was bounded by innate limitations in our ability. “Bounded rationality” meant that however much we might strive to make rational decisions, there were always limits of time and capacity. Real decision makers in real organizations “satisfice;” they settle for “good enough” answers.

Simon’s observation that theoretical rationality was bounded sparked a stream of research starting with Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman that gradually articulated the extent of the various failure modes of rational thought and established the field of behavioral economics. Kahneman’s 2011 book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, provides an excellent entry point into this realm.

Where do you start?

Suppose I’ve made a good enough case. You’d like to begin operating in a more intentional “pracademic” mode. What do you do next? Based on my own travels along this path I can suggest a 2-part reading list and some new practices to adopt.

The reading list contains some core theory and introductions to a starter set of practices.

Core Theory Readings

- Drucker, Peter F. 2017. The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done (Harperbusiness Essentials). US: Harperbusiness.

- Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. US: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Ong, Walter J. 2002. Orality and Literacy : The Technologizing of the Word (New Accents). US: Routledge.

- Schon, Donald A. 2008. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think In Action. US: Basic Books.

- Simon, Herbert Alexander. 1995. The Sciences of the Artificial. US: MIT Press.

Starter Practices Readings - Adler, Mortimer Jerome. 1971. How to Read a Book. US: Simon & Schuster (Paper).

- Ahrens, Sönke. 2017. How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking – for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers

- Morville, Peter. 2018. Planning for Everything: The Design of Paths and Goals. US: Semantic Studios.

- Newport, Cal. 2016. Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. US: Grand Central Publishing.

- Young, Scott, and James Clear. 2019. Ultralearning: Master Hard Skills, Outsmart the Competition, and Accelerate Your Career. HarperBusiness.

Starter Practices

There are three foundational practices that should be part of your repertoire.

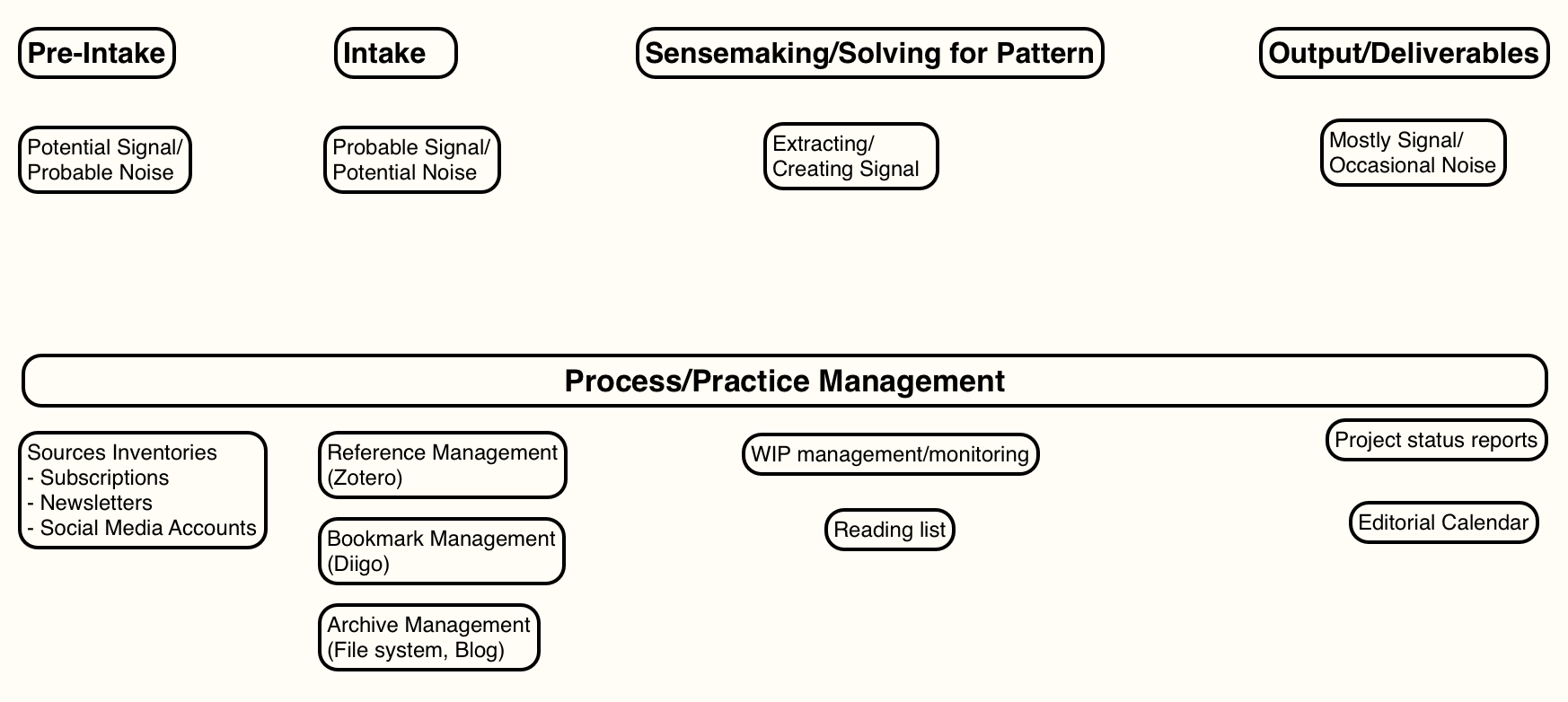

The first is one you likely already possess; a systematic reading habit. Actually, any reading addiction is a good starting point (cereal boxes were my gateway drug). Over time, you’ll likely find it worthwhile to put some support systems around your habits. There’s a reason your professors wanted you to produce bibliographies to accompany your work. Unfortunately, they sometimes forget to explain the why behind the what. Why and how to keep track of what you read is a subject of its own. We’ll save that for another day. For now, if you don’t have a tool to manage this practice, I suggest you take a look at Zotero | Your personal research assistant.

Reading is the fuel for your own thinking. The second core practice you want to invest in here is better note-taking. That’s covered excellently in Sönke Ahrens How to Take Smart Notes in the core reading list. I’ve got a review of his book here - Unexpected Aha Moments – Review – How to Take Smart Notes. I would also suggest taking a look at Getting Outside Your Head.

Over time your note-taking will evolve into note-making as you become more practiced in using your reading to engage in asynchronous conversations with writers. You’re going to want to start engaging in conversations with yourself, which is the third core practice. There are multiple approaches to developing a journaling habit. While journaling is often associated with doing emotional reflection and work, it’s also a tool for doing intellectual reflection and work.

What comes next?

You are now on a lifelong learning path. Perhaps you were already on it and now have some new tools to work with. You will discover that you’re walking this path with others on similar journeys. Strike up a conversation and share your discoveries.

McGee’s Musings turns 19 today. I started this outpost on the Web nineteen years ago while I was on the faculty of the Kellogg School. It was a way to share ideas with my students. It also grew out of my abiding interest in doing knowledge work effectively.

McGee’s Musings turns 19 today. I started this outpost on the Web nineteen years ago while I was on the faculty of the Kellogg School. It was a way to share ideas with my students. It also grew out of my abiding interest in doing knowledge work effectively.

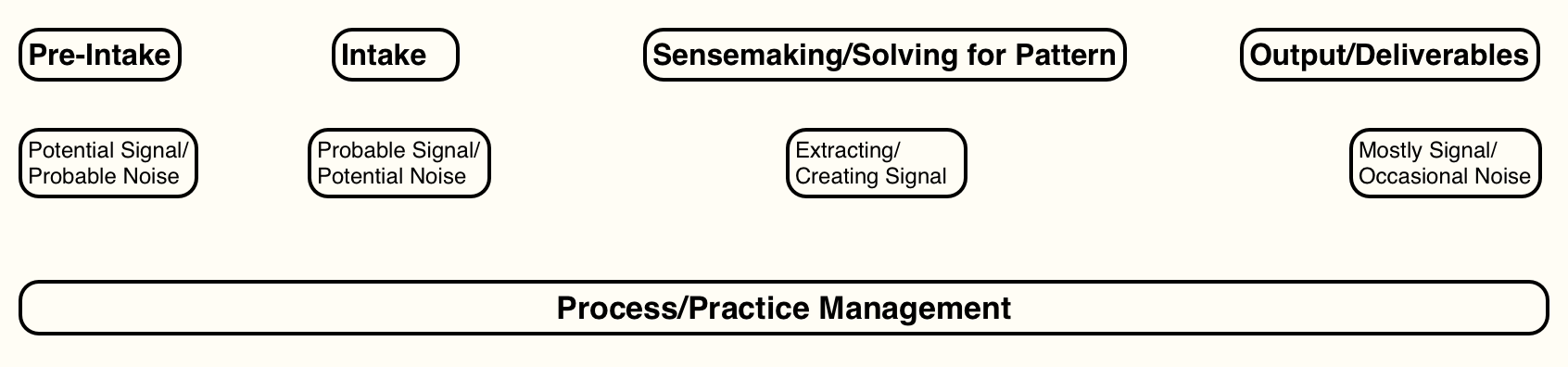

I’ve been deeply immersed in the recent profusion of new ideas, apps, and initiatives in the knowledge work

I’ve been deeply immersed in the recent profusion of new ideas, apps, and initiatives in the knowledge work I first encountered the notion of “affordances” in

I first encountered the notion of “affordances” in