Back in the earliest days of my third cycle of higher education, my advisor commented that this was the last opportunity I would have to invest in building my store of intellectual capital. I think this was his way of justifying the two books a week he was assigning in his doctoral seminar, the 50-page reading list in our organizational theory seminar, and the comparable workloads in industrial economics and research methods.

Back in the earliest days of my third cycle of higher education, my advisor commented that this was the last opportunity I would have to invest in building my store of intellectual capital. I think this was his way of justifying the two books a week he was assigning in his doctoral seminar, the 50-page reading list in our organizational theory seminar, and the comparable workloads in industrial economics and research methods.

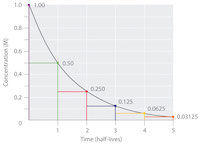

I did ultimately earn the piece of paper certifying me as an expert. But my advisor was wrong about that store of intellectual capital. Neither of us correctly factored in the half life of knowledge in the technology, data, and information realms we inhabited. You can’t build an academic career mining the work you did in graduate school. In today’s world, you can’t build any kind of career mining what you used to know.

This creates a new kind of learning problem. How do you approach learning if you’re already an expert? How do you manage the process of acquiring new knowledge when you are creating it at the same time?

I want to figure out what it means to do expert learning. I suspect the answers will look more like exploratory research than like taking a class from the designated expert. Your task isn’t so much to follow a curriculum as it is to design one in real time.

Perhaps what I’m working out here is an expanded definition of being an expert. We talk about SMEs—subject matter experts. Being a SME implies that you possess a particular knowledge base—a body of knowledge—plus knowledge of deeper principles and themes that aren’t readily apparent to the less expert.

Experts also know who the other experts are and hang out with them. We call these communities of interest and practice when we’re trying to impress people.

Finally, there has to be another layer of skill/expertise. You need a collection of methods and practices for updating, extending, and refactoring your existing knowledge base. There also needs to be a level of mindfulness about this layer. Maintaining and extending expertise has to be an explicit and deliberate practice.

I used to think it would be cool to go to school permanently. Turns out that the modern world requires it. Everybody has become a lifelong student. The part that got left out was that we are also expected to be lifelong teachers as well.

We think of learning relative to a body of knowledge; we talk about learning a foreign language, data science, corporate finance, or carpentry. Academic degrees are built around demonstrating mastery of a body of knowledge.Professions are defined and certified in terms of mastering a specified body of knowledge.

We think of learning relative to a body of knowledge; we talk about learning a foreign language, data science, corporate finance, or carpentry. Academic degrees are built around demonstrating mastery of a body of knowledge.Professions are defined and certified in terms of mastering a specified body of knowledge. Dunkin Donuts ran a legendary ad campaign in the 1980s—“Time to Make the Donuts.†You can still find the

Dunkin Donuts ran a legendary ad campaign in the 1980s—“Time to Make the Donuts.†You can still find the  Â

“Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand and I will move the Earth†doesn’t work if you are standing in the wrong place.

“Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand and I will move the Earth†doesn’t work if you are standing in the wrong place. Measure What Matters: How Google, Bono, and the Gates Foundation Rock the World with OKRs

Measure What Matters: How Google, Bono, and the Gates Foundation Rock the World with OKRs While there’s no obligation to explain your process to anyone, working it out for yourself does matter. There’s an observation from Aldo Leopold that’s pertinent:

While there’s no obligation to explain your process to anyone, working it out for yourself does matter. There’s an observation from Aldo Leopold that’s pertinent: I thought of starting this piece with an observation that talking about my process risked spiraling out of control until I realized that feeling was, in fact, a part of my process. The most satisfying part of my work is bringing new things into existence. An essential step is generating enough raw material to ensure that something good and pleasing is likely to emerge

I thought of starting this piece with an observation that talking about my process risked spiraling out of control until I realized that feeling was, in fact, a part of my process. The most satisfying part of my work is bringing new things into existence. An essential step is generating enough raw material to ensure that something good and pleasing is likely to emerge