An occupational hazard of acquiring a Ph.D. is adding lots of fancy new words to your vocabulary. Too often, these new terms devolve into weapons in status games. Sometimes, however, they clarify assumptions you didn’t realize you were making. “Nomothetic†and “idiographic†are terms you don’t pick up in casual conversation. They represent two distinct perspectives on making sense out of the world that explain a journey I’ve been on for years.

Let’s start with how the terms are defined;

- nomothetic – relating to the study or discovery of general scientific laws.

- idiographic – relating to the study or discovery of particular scientific facts and processes, as distinct from general laws.

Physics is all about the nomothetic; E=mc2 is true regardless. Economics aspires to be nomothetic, experience with trickle-down economics notwithstanding. Understanding Amazon or Apple, however, depends very much on the particulars of Jeff Bezos or Steve Jobs.

My own intellectual journey has been from the nomothetic to the idiographic. I was comfortable with mathematics and the hard sciences. Identify the problem, select the appropriate equation, crank the numbers and pop out the one right answer.Â

I thought I would study psychology as an undergraduate but opted for statistics instead. I told myself this was because I was more interested in studying people than pigeons or rats. In retrospect, I wasn’t ready to accept that the messiness and particularity of human behavior as something you could study as a scientist.

Computer programming and systems design were holding actions trying to cling to the general and the universal. Debits and credits worked for all organizations and all situations. I could treat the vagaries of individual executives as mere noise within a larger system of order and predictability.Â

I might have held onto that illusion if I hadn’t garnered a spot in the MBA program at the Harvard Business School. Now I was at the center of the case study universe; the particulars anchored every discussion. I still didn’t have the words in my lexicon but I had begun the journey from the nomothetic to the idiographic; from the general to the particular.Â

My comfort with individual courses correlated closely with where they fell on the spectrum from conceptual to concrete. Economics and accounting made sense, so did operations and finance. Marketing was a puzzle. Organizational behavior was mystifying; why did people insist on doing irrational things?Â

My personal life was largely irrational at this point. Courtesy of wise friends I was getting professional help for that, but I still clung to a fading vision of systems and order. I went back to consulting and systems design. There were right answers to be developed and deployed. Resistance to those right answers was an aberration (if not an abomination) to be suppressed and eliminated.Â

I could have pursued a classic strategy of accumulating enough power to impose my answers over the objections of weaker players. I’ve watched “my way or the highway†work (for certain values of “workâ€). I chose another path. I went back to sit at the feet of people smarter and more knowledgeable than I. What more could I learn from those who started by accumulating stories and case studies? I’ve written about this beforeÂ

This was where I finally learned of the distinction we’ve been talking about between nomothetic and idiographic. It’s comforting to discover that you are not the only one engaged in an important struggle.Â

How we come to know things isn’t a conversation that happens in the average business context. In a world dominated by knowledge work and innovation, however, it’s a conversation that needs to move center stage.Â

Organizations push for standardization and uniformity – this solves problems that organizations have to deal with. In the realm of knowledge work we have been too quick to assume generality before we’ve gathered enough data and insight about the richness and variety of actual practice.

In Ph.D. speak, nomothetic claims about human systems have to be filtered through an idiographic lens.Â

That isn’t a sentence I would want to utter in a boardroom. What I would advocate instead is to drop one common phrase and substitute another.Â

Stop talking about “connecting the dots.†Buried in that phrase is an assumption that there is already a right answer hiding in plain sight. The only work to be done is correctly recognizing the picture that exists. The particulars of this situation, in this moment, are mere noise obscuring what should be readily obvious.Â

If you’ve come to hold the particulars in higher regard, then you will be better served to frame your task as that of “solving for pattern.†I’ve written about this shift of perspective before

There are no equations that we can plug data into and expect a clear answer. But for all the particulars in any new case, there are regularities and patterns we can use in shaping effective responses.

I stumbled across an interesting opinion piece in the Washington Post recently;

I stumbled across an interesting opinion piece in the Washington Post recently;  In the early weeks and months of getting Diamond off the ground, we were intentional about the kind of organizational culture we wanted to create. Within the founding group we had decades of cumulative experience, mostly in organizations known for the strength of their culture together with a sprinkling of less pleasant experiences.

In the early weeks and months of getting Diamond off the ground, we were intentional about the kind of organizational culture we wanted to create. Within the founding group we had decades of cumulative experience, mostly in organizations known for the strength of their culture together with a sprinkling of less pleasant experiences. One of my bad habits is obsessing about my deficiency of good habits. I know that good habits are important because the nuns and monks were relentless in telling me so; decades later their ambivalence about my academic success without suitable discipline still lingers.

One of my bad habits is obsessing about my deficiency of good habits. I know that good habits are important because the nuns and monks were relentless in telling me so; decades later their ambivalence about my academic success without suitable discipline still lingers. The notion of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) is experiencing something of a renaissance. This rebirth is being driven by a combination of new apps, new ideas, and new thinkers promoting their wares. The apps, ideas, and thinkers are all worth paying attention to. At the same time. the brightness of shiny new things is obscuring important history and context.

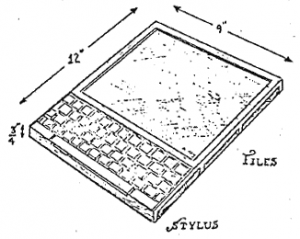

The notion of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) is experiencing something of a renaissance. This rebirth is being driven by a combination of new apps, new ideas, and new thinkers promoting their wares. The apps, ideas, and thinkers are all worth paying attention to. At the same time. the brightness of shiny new things is obscuring important history and context.