Wouldn’t the world truly be a better place if it did work like a musical? Who doesn’t appreciate a crowd breaking into spontaneous song and dance? Hat tip to Judy Breck of Smart Mobs for point this out.

Wouldn’t the world truly be a better place if it did work like a musical? Who doesn’t appreciate a crowd breaking into spontaneous song and dance? Hat tip to Judy Breck of Smart Mobs for point this out.

Suppose you buy the notion that management is fundamentally an oral culture and analytics a literate one (see Part 1). How does that influence how you manage analytics? How can you take full advantage of technology?

In an oral culture, what you can think is limited to what you can remember and tell–without visual aids. Oral thinking is linear, additive, redundant, situational, engaged, and conservative. The invention of writing and the emergence of literate cultures allows a new kind of thinking to develop. Literate thinking is subordinate, analytic, objectively distanced, and abstract. It’s the underlying engine of science and the industrial revolution.

Management understands something that those rooted in literate thinking may not. Knowing the right answer analytically has little or nothing to do with whether you can get the organization to accept that answer. What literate thinkers dismiss as "politics" is the essential work of translating and packaging an idea for acceptance and consumption in an oral culture.

The critical step in translating from a literate answer to an oral plan of action is finding a story to hang the answer on. The analysis only engages the mind; moving analysis to action must engage the whole person. Revealing this truth to the analytical minded can be discomforting. It’s equivalent to explaining to an accountant that the key to a Capital Expenditure proposal is theater, not economics. You might want to check out Steve Denning’s book, "The Springboard: How Storytelling Ignites Action in Knowledge-Era Organizations," for some good insights into how to craft effective stories inside organizations.

In addition to helping the analytically biased see the value of creating a compelling story, you need to help them see how and why story works differently than analysis. The best stories to drive change are not complex, literary, novels. They are epic poetry; tapping into archetypes and clich , acknowledging tradition, grounded in the particular. You need to bring them to an understanding of why repetition and "staying on message" is key to shifting an oral culture’s course, not an evil invention of marketing.

Assume you teach the literate types in your analytic organization how to repackage their analyses for consumption. They’ve now learned how to pitch their ideas in ways that will stick in the organization. What might you learn from their literate approach to thought? Is there an opportunity if you can get more of your organization and more of your management operating with literate modes of thinking?

Being able to write things down done permits you to develop an argument that is more complex and sophisticated. On the plus side, this makes rocket science possible. On the negative side, you get lawyers.

On the other hand, if you are operating in an environment whose complexity demands a corresponding complexity in your organizational responses, then encouraging more literate thinking by more members of the organization is a good strategy.

What would such an organization look like compared to today’s dominant oral design? The mere presence of e-mail and an intranet is insufficient. E-mail tends to mirror oral modes of thought, particularly among more senior executives. Intranets tend to be over-controlled and, to the extent they contain examples of literate thinking, are rooted in an organizational culture that strives to confine the literate mind to the role of well-pigeonholed expert. The presence of particular tools, then, isn’t likely to be a good predictor, although their absence might be.

What of possible case examples? A few knowledge management success stories hold hints. Buckman Labs used discussion groups successfully to get greater leverage out of its staff’s knowledge and expertise. Whether this success built on literate modes of thought or simply on better distribution of oral stories is less clear. The successes of some widely distributed software development teams are worth looking at from this perspective.

Although it’s a bit too early to tell, the take up of blogs and wikis inside organizations may be a harbinger of management based on literate thinking skills. They offer an interesting bridge between the oral and the literate by providing a way to capture conversation in a way that makes it visible and, hence, analyzable. As a class of tools, they begin to move institutional memory out of the purely oral and into the realm of literate.

Have you ever wondered what’s behind the conflict between geeks and suits? Sure, they think differently, but what, exactly, does that mean? A Jesuit priest who passed away in 2003 at the age of 90 may hold one interesting clue.

Walter Ong published a slim volume in 1982 titled "Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word" that explored what the differences between oral and literate cultures mean about how we think.

Remember Homer, the blind epic poet credited with "The Iliad" and "The Odyssey"? If we remember anything, it’s something along the lines of someone who managed to memorize and then flawlessly recite book-length poems for his supper.

The real story, which Ong details, is more interesting and more relevant to our organizational world than you might suspect. Homer sits at the boundary between oral culture and the first literate cultures.

In an oral culture, what you can think is limited to what you can remember and tell–without visual aids. Ong’s work shows that oral thinking is linear, additive, redundant, situational, engaged, and conservative. The invention of writing and the emergence of literate cultures allows a new kind of thinking to develop: literate thinking is subordinate, analytic, objectively distanced, and abstract. It’s the underlying engine of science and the industrial revolution.

While this may sound interesting for a college bull session, it’s particularly relevant to organizations. For all their dependence on the industrial revolution, organizations are human institutions first. Management is fundamentally an oral culture and is most comfortable with thought organized that way. Historically, leadership in organizations went to those most facile with the spoken word.

At the opposite extreme, information technology is a quintessentially literate activity with a literate mode of thought. In fact, IT cannot exist without the objective, rational, analytical thinking that literate culture enables.

How does the nature of this divide complicate conversations between IT and management? Can understanding the differing natures of oral and literate thought help us bridge that divide?

Technology professionals have long struggled with getting a complex message across to management. In our honest and unguarded moments, we talk of "dumbing it down for the suits." But the challenge is more subtle than that. We need to repackage the argument to work within the frame of oral thought. The easy part of that is about oratorical and rhetorical technique. The more important challenge is to deal with the deeper elements of oral culture; of being situational, engaged, and conservative. The right abstract answer can’t be understood until it is placed carefully within its context.

What management recognizes in its fundamentally oral mind is that organizations and their inhabitants spend most of their time in oral modes of thought. The oral mind is focused on tradition and stability because of how long it takes to embed a new idea. The techniques of change management that seem so obtuse to the literate, engineering mind are not irrational; they are oral. They are the necessary steps to embed new ideas and practices in oral minds.

Repeating a calculation or an analysis is nonsense in a literate culture. Management objections to an analytical proposal rarely turn on objections to the analysis. Walking through the analysis again at a deeper level of detail will not help. What needs to be done is to craft the oral culture story that will carry the analytical tale. It’s not about dumbing down an argument, it’s about repackaging it to match the fundamental thought processes of the target audience.

That might mean finding the telling anecdote or designating an appropriate hero or champion. Suppose, for example, that your analysis concludes it’s time to move toward document management to manage the files littering a shared drive somewhere or buried as attachments to three-year old e-mails. Analytical statistics on improved productivity won’t do it. A scenario of the "day in the life" of a field sales rep would be better. Best would be a story of the sales manager who can’t find the marked up copy of the last version of the contract.

These human stories are much more than the tricks of the trade of consultants and sales reps. They are recognition that what gets dressed up as the techniques of change management are really a bridge to the oral thinking needed to provoke action.

Seen in this light, what is typically labeled resistance to change is better understood as the necessary time and repetition to embed ideas in an oral environment.

Paula Thornton, my friend and co-blogger at FASTforward, tweeted the following this morning

which reminded me of a little constrained exercise I did back in February. That exercise started with this tweet

and a blog post that generated some fun discussion.

What I didn’t do was publish the final list of C-words that were ultimately generated in the ensuing discussion. Again, the constraint was C-words relevant to conversations about knowledge. Here’s the list (including "constrain/constraint" that all of you created:

| Calculate Calibrate Canvas Capture Catalog Categorize Censor Certify Challenge Change Characterize Chart Check Cite Claim Classify Cluster Circulate Circumscribe Circumvent Coalesce |

Coax Co-create Codify Collaborate Collate Collect Collude Combine Comment Communicate Compare Compile Compose Compute Concatenate Conceal Conceive Conform Confide Connect Connote |

Consider Consolidate Constrict Consult Constrain Constraint Construct Contribute Converse Convert Convey Coordinate Copy Count Craft Cram Create Critique Crystallize Cultivate Curate Customize |

Capital Case/Case Study Cause Channel Characteristic Chart Collage Community Compendium Competence Component Concept Concern Construct Content Context Convention Conversation Culture |

Coherent Complete Concise Conditional Consistent Contingent Contradictory Convergent Cryptic Current Cursory |

The following is an actual question given on a University of Washington chemistry mid-term. Hat tip to Annabelle Mark who is a constant source of this type of material

Bonus Question: Is Hell exothermic (gives off heat) or endothermic (absorbs heat)?

The answer by one student was so ‘profound’ that the professor shared it with colleagues, via the Internet, which is, of course, why we now have the pleasure of enjoying it as well

Most of the students wrote proofs of their beliefs using Boyle’s Law (gas cools when it expands and heats when it is compressed) or some variant. One student, however, wrote the following:

First, we need to know how the mass of Hell is changing in time. So we need to know the rate at which souls are moving into Hell and the rate at which they are leaving. I think that we can safely assume that once a soul gets to Hell, it will not leave. Therefore, no souls are leaving. As for how many souls are entering Hell, let’s look at the different religions that exist in the world today.

Most of these religions state that if you are not a member of their religion, you will go to Hell. Since there is more than one of these religions and since people do not belong to more than one religion, we can project that all souls go to Hell. With birth and death rates as they are, we can expect the number of souls in Hell to increase exponentially. Now, we look at the rate of change of the volume in Hell because Boyle’s Law states that in order for the temperature and pressure in Hell to stay the same, the volume of Hell has to expand proportionately as souls are added.

This gives two possibilities:

- If Hell is expanding at a slower rate than the rate at which souls enter Hell, then the temperature and pressure in Hell will increase until all Hell breaks loose.

- If Hell is expanding at a rate faster than the increase of souls in Hell, then the temperature and pressure will drop until Hell freezes over.

So which is it?

If we accept the postulate given to me by Teresa during my Freshman year that, ‘It will be a cold day in Hell before I sleep with you,’ and take into account the fact that I slept with her last night, then number two must be true, and thus I am sure that Hell is exothermic and has already frozen over. The corollary of this theory is that since Hell has frozen over, it follows that it is not accepting any more souls and is therefore, extinct……leaving only Heaven, thereby proving the existence of a divine being which explains why, last night, Teresa kept shouting ‘Oh my God.’

THIS STUDENT RECEIVED AN A+

Hell explained by a Chemistry Student

Tue, 13 Jan 2009 23:56:34 GMT

I’ve always been a bit mystified by the notion that these stories need to be set up as "an actual exam question" to make them worthy of reading. If I simply enjoy the story on its own (see Snopes for more background) does that mean that I’m somehow dull and boring? To me these are all in the category of the lyric from "Johnny Tarr:"

Even if you saw it yourself, you wouldn’t believe it,

But I wouldn’t trust a person like me, if i were you

I wasn’t there I swear i have an alibi

I heard it from a man who knows a fella who says it’s true!

1000 Times

Fri, 20 Mar 2009 04:00:00 GMT

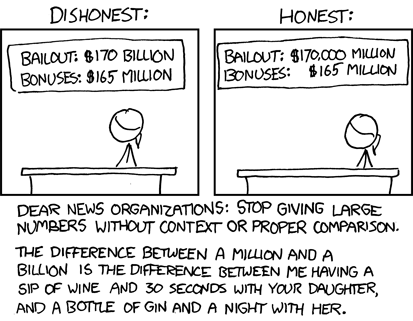

We live in complicated times. We’re all trying to make sense of what is going on. That sense making isn’t made any easier by lazy writing and thinking. Actually, I don’t think this is a matter of deliberate efforts to mislead so much as it represents a continuing laziness when it comes to dealing with numbers, particularly big ones.

Two good places to start if you want to improve your own ability to make sense out of the numbers getting thrown around are Guesstimation: Solving the World’s Problems on the Back of a Cocktail Napkin and Filters Against Folly : How to Survive Despite Economists, Ecologists, and the Merely Eloquent.

I’m just now on the tail end of dealing with accumulated bitrot in my Windows Vista tablet PC that is my primary computing environment. Most of it has gone smoothly, although the process can be tedious. Why you should need to reinstall the OS at periodic intervals remains a mystery to me.

Most of my backups and restores have worked smoothly. Of course, Microsoft is smarter than I am, so backing up and restoring Outlook files is not so simple. The upshot is that the best backup of my email is about a month old and I have lost emails that I’ve received since the end of February. If you’ve sent me something and haven’t heard from me, feel free to ping me again.

Some problems are so complex that you have to be highly intelligent and well informed just to be undecided about them.

– Laurence Peter

Dialogue Mapping: Building Shared Understanding of Wicked Problems, Conklin, Jeff

However you’re paying attention to the current external environment — the nightly news, newspapers, blogs, Twitter, or the Daily Show — it’s a grim time. While there is a great deal of noise, there’s not as much light as you might like. Dialogue Mapping, by Jeff Conklin, is one effort to equip us with tools for creating more light. While Conklin started out doing research on software for group decision support that research led him into some unexpected places of organizational dynamics and problem structure. He starts with the notion of “fragmentation” as the barrier to coherent organizational action. He defines fragmentation as “wicked problems x social complexity.”

I’m often surprised that the term “wicked problem” hasn’t become more common. The notion and the term have actually been around for decades. Horst Rittel at Berkeley coined the term in a paper, “Issues as Elements of Information Systems,” in the 1970s. Rittel identified six criteria that distinguish a particular problem as a wicked one:

Compare wicked problems with tame problems. A tame problem:

Obviously there are degrees of wickedness/tameness. Nevertheless, the real world of politics, urban planning, health care, business, and a host of other domains is filled with wicked problems, whether we acknowledge them as such or not. All too often, wicked problems go unrecognized as such. If you do recognize a problem as a wicked one, you can choose to attempt to tame it to the point where you might be able to solve it. Some ways to tame a wicked problem include:

These are the kinds of problem management strategies frequently seen in organizations. Conklin provides a good case that we and organizations would be better off if we were more explicit and mindful that this is what we were up to. That isn’t always possible and brings us to Conklin’s second element driving fragmentation: social complexity. Independently of the problem features that make them wicked problems, problems also exist in environments of multiple stakeholders with differing worldviews and agendas.

This social complexity increases the challenge of discovering or inventing sufficient shared ground around a problem to make progress toward a resolution or solution. This is where Conklin’s book adds its greatest value by introducing and detailing “Dialogue Mapping,” which is a facilitation technique for capturing and displaying discussions of wicked problems in a useful way.

Assume that someone recognizes that we have a wicked problem at hand and persuades the relevant stakeholders to gather to discuss it and develop an approach for moving forward. Assume further that the stakeholders acknowledge that they will need to collaborate in order to develop that approach (I realize that these are actually fairly big assumptions). More often than not, even with all the best of intentions, the meetings will produce lots of frustration and little satisfying progress. Our default practices for managing discussions in meetings can’t accommodate wicked problems, which is one of the reasons we find meetings so frustrating.

“Dialogue Mapping” takes a notation for representing wicked problems, IBIS (short for Issue-Based Information System) and adds facilitation practices suited to the discussions that occur with wicked problems. The IBIS notation was developed by Rittel in his work with wicked problems in the 1970s. It is simple enough to be largely intuitive, yet rich enough to capture conversations about wicked problems in useful and productive ways.

The building blocks of a dialogue map are questions, ideas, arguments for an idea (pros), and arguments against an idea (cons). These simple building blocks, together with what is effectively a pattern language of typical conversational moves, constitute “dialogue mapping.” The following is a fragment of a dialogue map that might get captured on a whiteboard in a typical meeting:

While the notation is simple enough, learning to use it on the fly clearly takes some practice. Some starting points for me are using it to process my conventional meeting notes and beginning to use the notation while taking notes on the fly. I’m not yet ready to employ it explicitly in meetings I am facilitating, especially given Conklin’s advice that the technique changes the role of meeting facilitator in some significant ways.

When applied successfully in meeting settings, Conklin argues that dialogue mapping creates a shared representation of the discussion that accomplishes several important things:

Much of the latter part of the book consists of showing how different conversational “moves” play out in a dialogue map. Assuming you are working with organizations that actually want to tackle wicked problems more productively, understanding these moves is immensely illuminating. Actually, it’s also illuminating if you’re in a setting where the incumbents aren’t terribly interested in the value of shared understanding. In those settings, you might need to keep your dialogue maps to yourself.

There are two software tools that I am aware of designed to support dialogue mapping. One is a tool called Compendium, which grew out of Conklin’s research. It is available as a free download and is built in Java, although it is not currently open source from a licensing point of view. The other is commercial tool called bCisive, developed in Australia by Tim van Gelder and the folks at Austhink. Here’s what a dialogue map in Compendium would look like. This particular map is a meta-map of the dialogue mapping process from 50,000 feet.

As I’ve spent time developing a deeper understanding of wicked problems and dialogue mapping it’s becoming clear that we have more of the former to tackle and we need the tools of the latter to wrestle with them. In this world, decisions don’t come from algorithms or analysis; they emerge from building shared understanding. In this world, to quote Conklin’s conclusion, “the best decision is the one that has the broadest and deepest commitment to making it work.” These are the tools we need to become facile with to design those decisions.

Here’s a fascinating animation reconstructing the flight of US Airways 1549 and overlaying the conversations between air traffic controllers and the flight crew. it really brings home the extraordinary job the crew did. A testament to the value of experience and training in responding to a crisis.

(h/t to Chris Carfi at the Social Customer Manifesto for the pointer]

Eat, Pray, Love is not the sort of book that I’m likely to pick up despite its tremendous success. Nevertheless, this TED talk by Elizabeth Gilbert, its author, is an excellent rumination and reflection on choosing the most effective emotional relationship between creativity and work. In a nutshell, the Greeks had it right in their notion of the Muses.

Elizabeth Gilbert on nurturing creativity | Video on TED.com