One of the many lovely things about blogging is the way that people redirect your attention to things you

Year: 2008

Attitude, hypothesis, experiment, and evidence

Doing science is fundamentally a state of mind more than any particular set of tools or any particular domain of knowledge.

How do you know when you’re doing science wrong?

Easy:

Read the comments on this post…

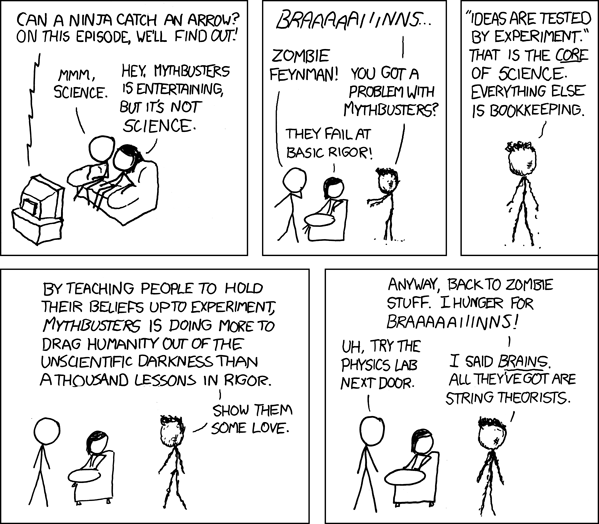

More in the same vein from xkcd.

Fostering these attitudes is increasingly relevant in organizational settings. We’re awash in data and in advocates of data mining, information analytics, super crunching, and other forms of extracting insight from the data. Too often, however, the emphasis elevates a new set of experts with a new set of mysterious tools saying “trust me.” Trusting them is no better than trusting your gut or someone else’s gut.

Fundamentally, the scientific method is no more than a method for how to be productively skeptical in the face of pressures and dispositions to believe and the multiple ways to be mistaken.

Grounded advice on making better use of your brain

John Medina is a molecular biologist bent on sharing how what we know about the brain can help us be more effective in the world at large. His central argument is that there are simple, but very important, lessons to be drawn from what science has learned in recent years about how the brain operates. Many of these lessons run counter to the practices and conventions that hold sway in our schools and organizations.

You can be pretty sure that I

Useful models of systems change

All models are wrong. Some models are useful.

George E.P. Box

Although we’re constantly engaged in attempts to improve systems and organizations by introducing new practices and technologies, we still tend to do a mediocre job of dealing with the ensuing organizational changes. Part of our problem is that we tend to rely on very simplistic models of organizational change, when we think about it at all. I’ve recently been revisiting the issue in the literature and in my work. The organizing framework that I’m finding most robust and useful comes originally out of the work of Virginia Satir, a family therapist who adopted a dynamic systems perspective of interaction that translates nicely into organizational settings. I came to Satir’s work by way of Gerry Weinberg, a long time student of technology and systems induced change.

The following diagram captures the essence of Satir’s model of systems change:

In this model, the change process starts with the introduction of some “foreign element,” which might be a new system or a new manager or a new performance mandate from on high, disrupting the “Old Status Quo.” “Chaos” ensues and performance both falls and becomes more erratic until a “transforming idea” develops or is introduced. This transforming idea constitutes a new theory about how to operate in the new system. With a good transforming idea in place, there is a period of integration and practice as the organization learns how to perform in its new configuration. Eventually, we reach a “New Status Quo” operating at a new, hopefully higher, level of performance.

There are a number of features of this model that I find valuable. First, it acknowledges that performance is always variable, even during periods of relative stability. It’s an important reminder that the systems we are talking about are made up of people and we must allow for their humanity. Second, it makes it clear that change is fundamentally a learning process not a deployment process. Moreover, it is “learning how” not “learning that,” which should help us keep in mind that things will get worse as an inevitable and necessary part of getting better and that the learning will take time.

Finally, there is the notion of a “transforming idea.” All too often, by the time we get to deployment, we’ve forgotten why we embarked on the journey to begin with. Articulating and sharing an effective transforming idea is an essential step in achieving the new levels of performance we are seeking. Human systems are homeostatic; they seek out and maintain stability. Absent a compelling transforming idea, these homeostatic forces will drag the system back to its current status quo. With a good “big picture” in mind, the participants in the changing system have a goal that can guide them through the necessary integration and practice.

Online Book Study Group Formed for Your Inner CEO

Earlier this year, I reviewed Your Inner CEO, by Allan Cox. In the course of that, I’ve actually had the pleasure of meeting Allan and getting to know him. I think it was Ross Mayfield of SocialText who introduced us. Allan is an existence proof that nice guys can be very successful.

One of the things I’ve been helping Allan with is understanding how new technology tools can help him get his ideas out there. One thing we’ve come up with is to make use of the great social media tools at Ning to support a community of those interested in the ideas in the book and in Allan’s work. To wit, here’s an announcement from Allan of an online book group for the book.

Greetings, READERS!

A few people in the Your Inner CEO Community (yes, there is one) have been lobbying for the launch of an online study group for the book itself: Your Inner CEO. In the beginning I wondered about the practicality and

Scary thoughts on one all-too-possible near future

It may be time to get more serious about using PGP and learning about Tor. Little Brother takes us into a near-future version of San Francisco where Jack Bauer has clearly become the U.S. Attorney General. Marcus is a seventeen year-old high school student who likes to play video games, role play, and has it all figured out (he’s 17 after all). In the wrong place at the wrong time, Marcus gets swept up by Homeland Security after a terrorist attack, held for questioning for days, and released with the threat that he’ll be watched carefully to make sure that he behaves.

The world that Marcus returns to has ratcheted up both fear and surveillance to something on the wrong side of police state. He chooses to fight back mostly out of adolescent stubbornness coupled with enough technical expertise to be dangerous to both the nascent police state and to himself and his friends. Doctorow is becoming a better and better storyteller with each of his books and Little Brother motors along. I pretty much dropped everything I should have been doing to plow through it over the course of two days.

The book has its flaws. The bad guys tend to be caricatures. The “lessons” about various hacks and technologies sometimes slow things down, although not as much as you might think. Doctorow may have his agenda but he remembers that his first priority is to entertain. Along the way, he also manages to get you to think about his larger message.

Sketching your way to insights

One of the rules of thumb I learned in the early days of my consulting career was that your project wasn’t real until you had at least one napkin or placemat filed in your working papers with some sketch that captured the essence of what you were designing or trying to understand. Dan Roam’s new book, The Back of the Napkin, makes the same case and provides substantial insight and guidance on how to make those sketches more useful.

Artistic talent and skill is largely irrelevant to Roam’s discussion. He’s talking about drawing as a thinking tool and the value of simple pictures in understanding complex phenomena. While his work is rooted in deep understanding of how our visual system and brains work, Roam boils it down to simple and practical advice. He summarizes the book with an image of a Swiss Army knife. Here’s my very own sketch of that drawing:

The heart of Roam’s approach is a process of Look, See, Imagine, and Show. The distinction between Look and See is a bit subtle. In Roam’s formulation, Looking is somewhat more passive and is about taking in the raw materials of what is out there, while Seeing is a more active process of chunking and imposing order on those raw materials. Imagine moves away from our eyes to our mind’s eye where we can experiment with multiple representations of what we’ve seen and how we can make sense of it. Finally, Show is about working out ways to take someone else through the mental process that will help them see what we’ve come to see. Again, here’s my version of Roam’s model:

While a good picture may indeed be worth a 1000 words, Roam is no advocate of simply letting a picture speak for itself. He has two purposes with his book. The first is to equip you with better tools for using simple pictures to furthering your own understanding of problems. The second is to educate and convince you to put those tools to use in helping communicate your new understanding to others. Roam provides good advice about the kinds of pictures you should draw to address the classic journalistic questions (Who, What, Where, When, Why, How, and How Much). He also introduces a curious mnemonic, SQVID, which translates to Simple, Quality, Vision, Individual Attributes, and Delta. Each represents one pole in choices you can make when you are sketching a particular concept.

This is a rich and useful book. If you’re already a visual thinker, it offers a good organizing framework and collection of tools and techniques to add to your bag of tricks. If you’re not yet a visual thinker, this should provide you with the necessary encouragement to start.

Some inspiration on failure

I’m sure this will be making the rounds. It’s a good reminder about the value of failure. I found this courtesy of Brad Feld. Thanks for sharing.

Great, inspiring video on failure.

(thanks Scott).

Congratulations to Jack Vinson

One of the unexpected rewards of blogging is watching those that you’ve influenced in some way going off and succeeding in their own unique way. If for some odd reason you are not already following Jack’s work, you should correct that mistake immediately.

Blogging for five years

I have been blogging for five years now. Amazing. My focus has always been around knowledge management, but the specifics and surrounding topics have wandered over the years.

Thanks to all my commenters and readers. And a special thanks (again) to Jim McGee who told me, “You should really start your own blog” because I was leaving so many comments on his. (So many, in fact, that I still get spam that thinks I have something to do with the ownership of his website.)

Statistics:

- 1860 entries (this is number 1861)

- ~1900 readers via FeedBurner

- 1415 comments (many from myself)

- 419 trackbacks (many from myself)

- 28 categories with anywhere from 6 to 616 entries

- 1753 tags (and not all entries are tagged)

Blogging for five years

Jack Vinson

Sun, 18 May 2008 20:06:58 GMT

Technology for us – the heart of Enterprise 2.0?

The phrase “technology for us” has been kicking around in my head for the past several months. At the FASTForward ’08 conference, I took a first pass at articulating my thinking in a video interview with Jerry Michalski. Consider this my next attempt. I expect there will be more.

Technology for Them

Information systems in organizations generally have been “technology for them.” Accounting systems, inventory control systems, ERP systems, reservations systems are all designed and imposed on their users.

Done properly, these systems yield efficiencies, predictable quality, and significant economic benefits. The design and implementation processes for these systems are industrial engineering at its best. Expert designers observe, redesign, and streamline processes to define and constrain what the target user population is allowed to do.

In these systems, users are simply one component in a mechanistic environment designed to constrain behaviors. User roles are limited to situations where technology is too expensive and a human user is more economical. Individual creativity and initiative are neither desirable or appropriate.

Technology for Me

The personal computer revolution brought “technology for me.” We saw innovation and scores of programs designed to improve the productivity and effectiveness of individual knowledge workers. Few of us would go back to a world without spreadsheets, word processors, or the other tools made possible and accessible via personal level information technology.

The first waves of innovation in the PC world focused largely on individual productivity. Attention to work process, if any, was a function of the idiosyncrasies of each user. Broadly speaking, innovation took one of two forms. Programmers and developers generalized from their own needs to develop unique tools solving their own problems. With luck, those solutions found enough kindred spirits to sustain a market. Early examples here would include the original Visicalc, ThinkTank, More, and dBase. More recent examples would include MindManager, SketchUp, Powerpoint, and the Brain.

The alternate development path was more corporate, with planned attempts to meet the application needs of perceived large markets of individual information and knowledge workers. Examples here would include the original Lotus 1-2-3, Microsoft Word, and Visio.

This development path emphasized industrial and mechanistic conceptions of work. Moreover, the logic of mass markets produced products targeted to the perceived lowest common denominator of user needs. At its worst, this path leads right back to technology for them and Microsoft Bob as a distorted model of users and use cases.

Us as Knowledge Worker

There are two dimensions of “technology for us” worth exploring. The first is “us” as knowledge workers; individuals charged with “thinking for a living” in Tom Davenport’s coinage and expected to exercise substantial initiative and autonomy in the design and execution of their work. The second dimension of “us” is the degree to which key work products and deliverables emerge from the collective and coordinated action of multiple knowledge workers. We’ll return to this second form of us in a bit.

There are both political and practical problems with applying technology effectively to the unique needs of knowledge workers. Previous organizational uses of technology have not had to deal with situations where the target audience was free to ignore you. Knowledge workers occupy positions of power and influence within the enterprise. They have the power and inclination to ignore, dismiss, and actively undermine ill-conceived and poorly executed efforts to modify their work practices. For that matter, they have to power to dismiss well-conceived and well-executed efforts on their behalf.

If you’re smart enough to avoid the trap of trying to dictate an approach to this user community and actively engage them in the design and implementation process, you run into the next constraint. Knowledge workers can’t articulate quality, effectiveness, or efficiency with anything resembling the precision that applies to manual or information work. The nature of knowledge work and its deliverables makes typical measurement approaches suspect (see Crafting Uniqueness in Knowledge Work and The Invisibility of Knowledge Work, for example). We have only recently begun to understand individual knowledge work practices in ways that let us apply technology with some likelihood of success. In many ways we are still working out the details of the vision of knowledge work support first articulated by Vannevar Bush in the mid-1940s in As We May Think.

Us as Groups of Knowledge Workers

Organizations exist to solve problems beyond the capacity of individuals to tackle. This is as true of knowledge work as it is for all other types of work. For all the power of technology to make individual knowledge workers more productive and effective, the greater opportunity lies in developing skill at using technology to support collective activity.

What we haven’t yet done well is knit together our knowledge of how to improve group oriented work practices and technological possibilities. Further, the more promising efforts have seen limited penetration into organizations. When dealing with collective knowledge work we compound the problem of knowledge worker autonomy with the problem that the knowledge work processes we wish to improve are vague, imprecise, and squishy in ways quite uncharacteristic of the work processes we are comfortable working with in industrial settings.

If we take the analysis and improvement tools we are comfortable with in industrial process settings and simply port them to knowledge work environments, one of two things happens. Either, we become hopelessly frustrated trying to force a dynamic and fluid process into the confines of our swimlanes. Or, we mistake the small fraction of the process we can force fit into our tools for the entire phenomenon; guaranteeing that our target users will ignore us and route around our efforts.

While there are people who have thought about the problems of applying technology to complex knowledge work processes and practices, their work has not achieved the widespread adoption it needs to be a meaningful factor in most organizations. Some good entry points into this work include:

- Doug Engelbart. Toward High-Performance Organizations: A Strategic Role for Groupware

- Alan Kay. The Real Computer Revolution Hasn’t Happened Yet

- Dave Snowden. Cognitive Edge (Snowden’s blog may be the simplest place to start here; the papers tend to be a bit academic)

- Jeff Conklin. Wicked Problems and Social Complexity (pdf). Cognexus Institute

The inventory of technology solutions promising to streamline, improve, or transform group activities continues to grow, although it often seems more like baroque and rococo variations on a handful of themes than like new insights or frameworks. Will the next implementation of threaded discussion make any major contribution to educating a group on when and how to make effective use of that technique? Or to understanding what situations make it a poor choice of tool?

What seems to be missing is a synthesis of Group Behavior 101 and a groupware pattern language. I’m not aware of anything that would fit that bill, although Stewart Mader’s recent Wikipatterns might represent a potential starting point. Can anyone point to some examples I’m unaware of? Is this something that we should be working to develop?