David Reed is one of the creators of the underlying protocols and design that is the Internet. Here is a lengthy reflection from David on why those design decisions worked so well and why we ought to be very cautious about messing with them. It’s long and a bit dense. Read it anyway. The better you understand what David is saying here, the better you will be able to navigate and leverage the world he helped create. This is the world we live in; understand it.

David Reed is one of the creators of the underlying protocols and design that is the Internet. Here is a lengthy reflection from David on why those design decisions worked so well and why we ought to be very cautious about messing with them. It’s long and a bit dense. Read it anyway. The better you understand what David is saying here, the better you will be able to navigate and leverage the world he helped create. This is the world we live in; understand it.

The Internet must be fit to be the best medium of discourse and intercourse [not just one of many media, and not just limited to democratic discourse among humans]. It must be fit to be the best medium for commercial intercourse as well, though that might be subsumed as a proper subset of discourse and intercourse.

Which implies interoperability and non-balkanization of the medium, of course. But it also implies flexibility and evolvability – which *must* be permissionless and as capable as possible of adapting to as-yet-unforeseen uses and incorporating as-yet-unforeseen technologies.

I’ve used the notion of a major language of inter-cultural interaction, like English, Chinese, or Arabic, as an explicit predecessor and model for the Internet’s elements – it’s protocols and subject matter, it’s mechanism of self-extension, and it’s role as a “universal solventâ€.

We create English or Chinese or Arabic merely by using it well. We build laws in those frameworks, protocols of all sorts in those frameworks, etc.

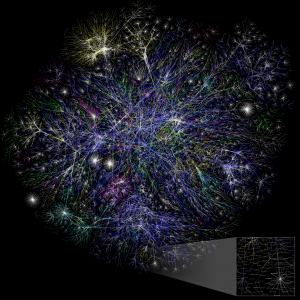

But those frameworks are inadequate to include all subjects and practices of discourse and intercourse in our modern digital world. So we invented the Internet – a set of protocols that are extraordinarily simple and extraordinarily independent of medium, while extensible and infinitely complex. They are mature, but they have run into a limit: they cannot be a framework for all forms of (digital information). One cannot encode a photograph for transmission in English, yet one can in the framework we have built beginning with the Internet’s IP datagrams, addressing scheme, and agreed-upon mechanics.

The Internet and its protocols are sufficient to support an evolving and ultimately ramifying set of protocols and intercourse forms – ones that have *real* impact beyond jurisdiction or “standards body”.

The key is that the Internet is created by its users, because its users are free to create it. There is no “governor†who has the power to say “no†– you cannot technically communicate that way or about that.

And the other key is that we (the ones who began it, and the ones who now add to it every day, making it better) have proven that we don’t need a system that draws boundaries, says no, and proscribes evolution in order to have a system that flourishes.

It just works.

This is a shock to those who seem to think that one needs to hand all the keys to a powerful company like the old AT&T or to a powerful central “coordinating body†like the ITU, in order for it not to fall apart.

The Internet has proven that the “Tower of Babel†is not inevitable (and it never was), because communications is an increasing returns system – you can’t opt out and hope to improve your lot. Also because “assembly†(that is, group-forming) is an increasing returns system. Whether economically or culturally, the joint creation of systems of discourse and intercourse *by the users* of those systems creates coherence while also supporting innovation.

The problem (if we have any) is those who are either blind to that, or willfully reject what has been shown now for at least 30 years – that the Internet works.

Also there is too much (mis)use of the Fallacy of Composition that has allowed the Internet to be represented as merely what happens when you have packets rather than circuits, or merely what happens when you choose to adopt certain formats and bit layouts. That’s what the “OSI model†is often taken to mean: a specific design document that sits sterile on a shelf, ignoring the dynamic and actual phenomenon of the Internet. A thing is not what it is, at the moment, made of. A river is not the water molecules that currently sit in the river. This is why the neither owners of the fibers and switches nor the IETF can make the Internet safe or secure – that idea is just another Fallacy of Composition. [footnote: many instances of the “end-to-end argument” are arguments based on a Fallacy of Composition].

The Internet is not the wires. It’s not the wires and the fibers. It’s never been the same thing as “Broadbandâ€, though there has been an active effort to confuse the two. It’s not the packets. It’s not the W3C standards document or the IETF’s meetings. It’s NONE of these things – because those things are merely epiphenomena that enable the Internet itself.

The Internet is an abstract noun, not a physical thing. It is not a frequency band or a “service†that should be regulated by one of the service-specific offices of the FCC. It is not a “product†that is “provided†by a provider.

But the Internet is itself, and it includes and is defined by those who have used it, those who are using it and those who will use it.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=a48bd95e-7bb5-42f6-9558-0608beff7e1e)