Some details about what my partner in collaboration, David Friedman, and I have been up to lately.

For the past few months, my colleague Jim McGee and I have been hard at work on a project we’ve named Collaborating Minds. It will be an online problem-solving community — with a unique membership recruiting strategy. The goal is to create a resource that will be able to assist organizations with hard problems by providing rich insights and multiple perspectives. It’s a marriage of some of the ideas of crowdsourcing with the principles that make for high performance teams. It’s an example of getting more people to work together better, a topic I wrote about a while back.Collaborating Minds’ main assets will be:

- Its network of 500-700 part-time participants

- Its approach to community building and structured problem solving,and

- Its software platform that supports and enables the community building and structured problem-solving.

The people will be recruited and selected based on their interest and ability to work together in the community in just the way the software platform allows. They will include people from a very diverse set of backgrounds. We’ll have scientists of various stripes, engineers of various types, humanists, consultants, experts in all kinds of fields. So in that respect it will be like crowdsourcing.

The community and the problem-solving will be actively managed, and the members will be expected to get to know at least some of the other community members outside the context of the specific problems we are working on. Community members will help each other on their own issues and challenges, and can use the problem-solving tools provided to do so if they like.

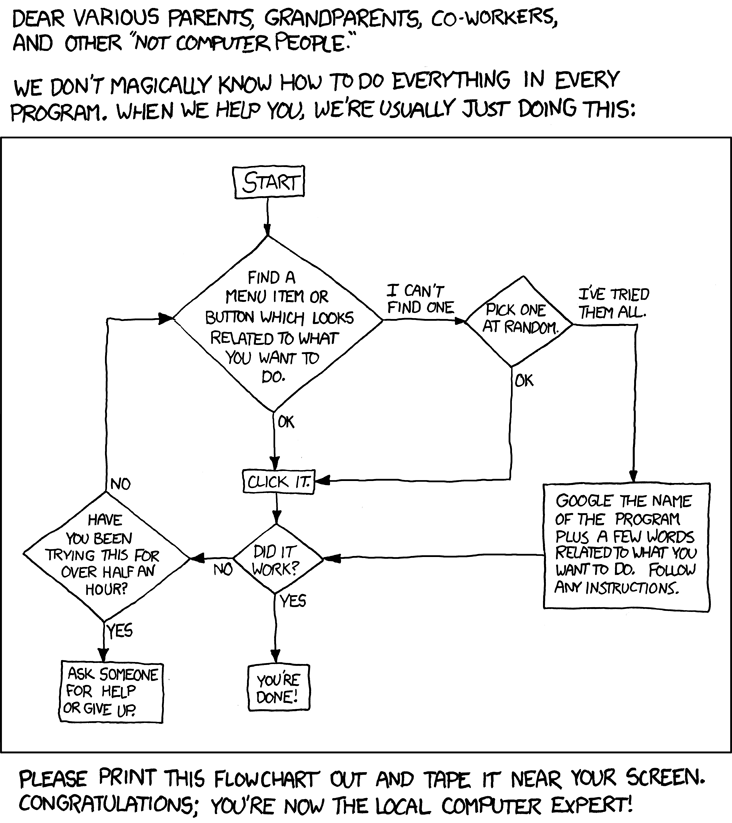

The software platform includes a social network of a particular kind, and a structured problem-solving process and spaces for the problem-solving to occur. The problem-solving method will combine structured asynchronous elements and structured synchronous elements (online meetings). We also will have an alternative free-form option for members to use when the structure isn’t right for the problem at hand.

There’s a lot more info available now at the Collaborating Minds site. We are almost finished with the alpha version of the software platform and are starting to talk with people about recruiting and membership. We have a lot of unanswered questions (e.g., precise target markets, compensation, and governance) and probably some wrong answers to others. One of the best things about this idea though, is that we can aim our group at ourselves; if this sort of group can generate insightful and powerful solutions to hard problems (which I believe it can) then it help us solve the issues that remain ahead.

Collaborating Minds

David Friedman

Fri, 24 Jun 2011 19:07:11 GMT

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=491b6f47-c2e1-4066-b13c-83c3a5283f6b)