I’ve carried a pocket knife since my days as a stage manager/techie in college. A handful of useful tools in hand beats the perfect tool back in the shop or office. Courtesy of the TSA I have to remember to leave it behind when I fly or surrender it to the gods of security theater but every other day it’s in my pocket. There is, in fact, an entire subculture devoted to discussions of what constitutes an appropriate EDC—Every Day Carry—for various occupations and environments.

I’ve carried a pocket knife since my days as a stage manager/techie in college. A handful of useful tools in hand beats the perfect tool back in the shop or office. Courtesy of the TSA I have to remember to leave it behind when I fly or surrender it to the gods of security theater but every other day it’s in my pocket. There is, in fact, an entire subculture devoted to discussions of what constitutes an appropriate EDC—Every Day Carry—for various occupations and environments.

I’ve been thinking about what might constitute the equivalent EDC or Swiss Army Knife for the demands of project planning and management. We live in a project based world but fail to equip managers with an appropriate set of essential project management tools.

Like all areas of expertise, project management professionals build their reputations by dealing with more complex and challenging situations. The Project Management Institute certifies project management professionals. PMBOK, the Project Management Book of Knowledge has reached its sixth edition and runs to several hundred pages.

The complexities of large-scale project management push much training and education into the weeds of work breakdown structures, scope creep, critical-path mapping, and more. The message that project management is a job for professionals and the amateur need not apply is painfully clear. But we’re all expected to participate in project planning, and often we must lead projects without benefit of formal training in project management.

Recently, I looked at the need for project design before project management. The essential problem is to use a picture of where you want to end up to lay out a map of how to get there from wherever you are now.

The end is where to begin. Until you can conjure a picture of where you want to go, you have no basis to map the effort it will take to create it. Imagine what you need to deliver in reasonable detail and you can work backwards to the steps that will bring it into being. If you have a clear sense of where you are, you can also identify the next few steps forward.

Working out the steps that will take you from where you are to where you want to go can be done with two tools and three rules.

Tool #1:Â A calendar. If you can do it all without looking at one, you aren’t talking about a project.

Tool #2:Â A messy outline. An outline because it captures the essential features of ordering steps and clustering them. Messy because you can’t and won’t get it right the first time and the neat outlines you were introduced to in middle school interfere with that. (Personally, I’m partial to mind maps over pure outlines, but that is a topic for another time.)

Three rules generate the substance of the outline:

- Small chunks

- First things first

- Like things together

“Small chunks†is a reminder that the only way to eat an elephant is in small bites. There are a variety of heuristics about recognizing what constitutes an appropriate small chunk of a project. Somewhere between a day and a week’s worth of work for one person isn’t a bad starting point. Writing a blog post is a reasonable chunk; launching a new blog isn’t.

Generating an initial list of small chunks is the fuel that feeds an iterative process of putting first things first, grouping like things together, and cycling back to revise the list of small chunks.

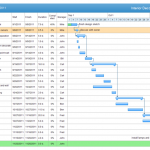

The art in project management lies in being clever and insightful about sequencing and clustering activities. Here, we’re focused on the value of thinking through what needs to be done in what order before leaping to the first task that appears. That’s why an outline is a more useful tool at this point than Gantt charts or Microsoft Project. An outline adds enough structure over a simple to do list to be valuable without getting lost in the intricacies of a complex software tool. An outline helps you organize your work, helping you discover similar tasks, deliverables, or resources that can be grouped together in your plans. An outline gives you order and clustering. The calendar links the outline to time. For many projects that will be enough. For the rest, it is the right place to start.

The point of a project plan is not the plan itself, but the structure it brings to running the project. The execution value of widespread project planning capability in the organization is twofold. First, it adds capacity where it is needed: at the grassroots level. Second, it improves the inputs to those situations where sophisticated project-management techniques are appropriate.

“Trust but verify” is no longer an effective strategy in an information saturated world. When Ronald Reagan quoted the Russian proverb in 1985, it seemed clever enough; today it sounds hopelessly naive. If we are reasonably diligent executives or citizens, we understand and seek to avoid confirmation bias when important decisions are at hand. What can we do to compensate for the forces working against us?

“Trust but verify” is no longer an effective strategy in an information saturated world. When Ronald Reagan quoted the Russian proverb in 1985, it seemed clever enough; today it sounds hopelessly naive. If we are reasonably diligent executives or citizens, we understand and seek to avoid confirmation bias when important decisions are at hand. What can we do to compensate for the forces working against us?

I’ve been writing at a keyboard now for five decades. As it’s Mother’s Day, it is fitting that my mother was the one who encouraged me to learn to type. Early in that process, I was also encouraged to learn to think at the keyboard and skip the handwritten drafts. That was made easier by my inability to read my own handwriting after a few hours.

I’ve been writing at a keyboard now for five decades. As it’s Mother’s Day, it is fitting that my mother was the one who encouraged me to learn to type. Early in that process, I was also encouraged to learn to think at the keyboard and skip the handwritten drafts. That was made easier by my inability to read my own handwriting after a few hours. Â I’m gearing up to teach project management again over the summer. There’s a notion lurking in the back of my mind that warrants development.

I’m gearing up to teach project management again over the summer. There’s a notion lurking in the back of my mind that warrants development. Â

Our admiration for the assembly line is so deep that we are suckers for the promise of “proven systems†regardless of their feasibility. We so treasure predictability and control that the promise seduces no matter how many times it is broken.

Our admiration for the assembly line is so deep that we are suckers for the promise of “proven systems†regardless of their feasibility. We so treasure predictability and control that the promise seduces no matter how many times it is broken.

Last time, we looked at the

Last time, we looked at the  I was a big fan of Sherlock Holmes and various other fictional detectives growing up; I’m still drawn to the form when I want to relax. There’s a basic pleasure in trying to match wits with Sherlock and figure our who the killer is before the final reveal. Connecting the dots is a rewarding game but it’s a flawed strategy.

I was a big fan of Sherlock Holmes and various other fictional detectives growing up; I’m still drawn to the form when I want to relax. There’s a basic pleasure in trying to match wits with Sherlock and figure our who the killer is before the final reveal. Connecting the dots is a rewarding game but it’s a flawed strategy.