The notion of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) is experiencing something of a renaissance. This rebirth is being driven by a combination of new apps, new ideas, and new thinkers promoting their wares. The apps, ideas, and thinkers are all worth paying attention to. At the same time. the brightness of shiny new things is obscuring important history and context.

The notion of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) is experiencing something of a renaissance. This rebirth is being driven by a combination of new apps, new ideas, and new thinkers promoting their wares. The apps, ideas, and thinkers are all worth paying attention to. At the same time. the brightness of shiny new things is obscuring important history and context.

At the risk of sounding like a grumpy old man yelling at people to get off of his lawn, I thought it would be helpful to look at some of that context in the hopes that it might make it less likely that we would repeat old mistakes. We should at least strive to make interesting new mistakes.Â

If you set aside the notion that knowledge management could arguably be considered a synonym for library science, what we label knowledge management in organizations today was born in the late 1980s/early 1990s in the efforts of a number of knowledge intensive organizations (HP, IBM, Accenture, McKinsey, Toyota, etc.) to systematically leverage the things inside their workers’ heads. Chief Knowledge Officers were appointed (a hat I once wore), taxonomies were defined, religious debates were held over the relative merits of Lotus Notes and Microsoft Sharepoint. Today, knowledge management is a reasonably well-defined function within most large organizations.Â

Enterprise knowledge management was built on the premise that the number of knowledge workers whose knowledge mattered enough to manage was a small and easily identified subset of the workforce as a whole. Knowledge management was a hedge against having the knowledge in those smart heads walk out the door.Â

The knowledge management problem changes when the proportion of the workforce classified as knowledge workers represents a significant fraction of the workforce. When everyone is a knowledge worker, knowledge management becomes personal not organizational.

A classic enterprise knowledge management problem is that of persuading the knowledgeable to share their knowledge with the rest of the enterprise. The naive hypothesis was that knowledge workers hoarded knowledge to preserve and protect their organizational status and position. A slightly less cynical take was that knowledge workers needed help to unpack and externalize their expertise so that it could be shared.Â

My take is that the average knowledge worker has no clue about what it would mean to manage their knowledge and no useful models to emulate. You see individual executives and knowledge workers using email as their primary knowledge storage structure. You see arguments that enterprise search engines will bring Google inside the organization and prove sufficient to find and reuse knowledge assets when the time comes. You see elaborate folder and directory structures trying to impose order on proliferating documents and deliverables.Â

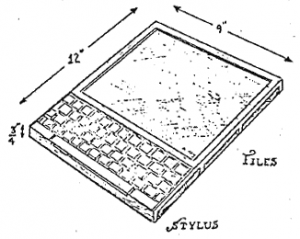

The rise of personal computing and the web encouraged some knowledge workers to experiment with better ideas. Wikis, blogs, and bookmark managers were pressed into service. Ideas that were ahead of the technology curve (Memex, Augmentation, Dynabook, Mundaneum, and, recently, Zettelkasten) have been dusted off and revisited.Â

The latest round of innovation and experimentation holds great promise. As an individual knowledge worker, you have several choices. One is to do nothing and wait for the dust to settle. A second is to place your bet on one of the current players and hope your support contributes to that player becoming the winner.Â

A third strategy—and the one I am pursuing—is to recall an observation Peter Drucker once made about the productivity gains made during the early years of the 20th Century;

Whenever we have looked at any job – no matter how many thousands of years it has been performed – we have found that the traditional tools are wrong for the task.

Peter Drucker

Those extraordinary gains flowed from examining tools and task and rethinking the combination in parallel. Changing tools without changing the task is a recipe for speeding up the mess. Changing tasks without rethinking tools will make the current mess a morass.

Personal knowledge management has to be one component of a personal quest to become a more effective knowledge worker.

Completely agree that personal knowledge management is getting very important these days. It might also be helpful if you could collaborate with your team about the thoughts that you had over the day. You also briefly mention the Zettelkasten method. I’m using it for my studies currently. While it was hard to get into, it works quite well when are used to it. We recently released a beginners guide to it if you want to check it out. https://zenkit.com/en/blog/a-beginners-guide-to-the-zettelkasten-method/