In April, 2003, the late Doug Engelbart gave the Keynote Address at the World Library Summit in Singapore; “Improving Our Ability to Improve.” The talk is an excellent entry point to one of his most powerful ideas. He also raises a specific question that I suspect wormed its way into my thinking back when I first encountered it.Â

In April, 2003, the late Doug Engelbart gave the Keynote Address at the World Library Summit in Singapore; “Improving Our Ability to Improve.” The talk is an excellent entry point to one of his most powerful ideas. He also raises a specific question that I suspect wormed its way into my thinking back when I first encountered it.Â

As an aside, I wish I could reconstruct the concatenation of events that led me to revisit the talk yesterday. I’m confident it was a revisit because I’ve been following Engelbart’s work for a long time and this piece was already in my systems. My note-taking and reading management systems are not so well-constructed, however, that I could do more than recall the essence of the piece. On the other hand, returning to old source materials can pay dividends. The source may not change but my perspectives evolve.

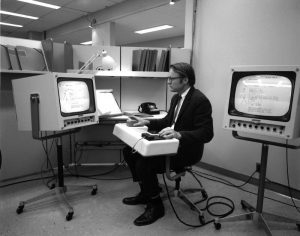

Engelbart’s career was dedicated to exploring how information technology could augment human intelligence rather than displace it. He was especially interested in how that partnership could attack big, complex, problems.Â

Shovels and bulldozers, to borrow and extend Engelbart’s analogy, both move dirt. If you have a lot of dirt to move, a single shovel isn’t your best choice. If no one has managed to invent a bulldozer yet, you might be limited to shovels but you aren’t limited to a single shovel.Â

Given a collection of shovels (and shovelers), you can organize the problem of moving dirt into a process. Process is an amplifier. With a layer of process in place, you can get further amplification by looking for ways to improve the process. Engelbart identifies one additional amplifier; improving how we do improvement. Engelbart labels these three amplifiers as A-activity, B-activity, and C-activity. It’s a simple enough model, but simple models can be very powerful.Â

At the base (“A-activity” in Engelbart’s terminology), you have the realm of process; the monthly billing cycle, managing trouble-tickets at the help desk, the assembly line turning out Toyotas. The economy is built on transforming ad hoc practices into standard operating procedures and repeatable processes.

Repeatable processes that produce repeatable outputs open up the possibility of systematic improvement. What changes can you make to the process while holding the outputs constant? Process improvement (the “B-activity” in Engelbart’s model) is the realm of quality management, business process re-engineering, and continuous improvement. It’s an amplifier of benefits flowing from repeatable processes.

As an organization accumulates more experience with process improvement and more opportunities for process improvement surface, there’s another level of leverage in investigating how you can get better at those improvement processes (“C-activity”).

What Engelbart is doing here is employing a classic computer science problem solving strategy; adding a new layer of indirection or abstraction. Rather than attack a problem head on, step back from the immediate features and adopt a new perspective. Engelbart explores this three-tier model in more depth in Toward High\-Performance Organizations: A Strategic Role for Groupware \- 1992 \(AUGMENT,132811,\)Â \-Â Doug Engelbart Institute.

Returning to the keynote address, Engelbart launches into a bit of a rant about “ease of use” and letting the market decide what features and functions should be available. He isn’t a fan. As I was nodding along, Engelbart posed a question that grabbed my attention;Â

Doesn’t anyone ever aspire to serious amateur or pro status in knowledge work?

If your answer is yes, then you have a problem in the context of the current information technology market and the purchasing preferences of most organizations. Those forces favor tools and services targeted toward beginner and intermediate levels of expertise. Think of the standard software installed on the typical corporate workstation. What training is provided on how to take full advantage of even those tools?

Reaching expert level performance in any field doesn’t happen by accident or by the simple accumulation of experience. It requires deliberate practice and a commitment to operate across multiple levels of perspective.