I’ve talked before about Peter Drucker’s recent thinking about how to improve the productivity of knowledge work. Productivity improvement is driven by a process of observing how work gets done and rethinking, redesigning, and tweaking the process so that fewer inputs and less effort go into producing the same quantity of output.

Essential to that improvement is the ability to define outputs and inputs precisely and to observe the transformation process carefully. Ideally you treat a task as a white box that you open up and play with. A fallback, and less effective, approach, when the process is hard to observe, is possible if you can still observe the outputs. You treat the process as a black box and constrain inputs or tighten cycle time standards. As long as you can observe the outputs and measure them with some accuracy, you can get some degree of productivity improvement simply out of being demanding.

As weak a management strategy as this may be, it can work tolerably as long as you can agree on how to measure the outputs. Unfortunately, it fails utterly as a management strategy when the outputs are difficult to characterize – i.e. for most of knowledge work. The most typical alternative strategy doesn’t help. That is to shift focus from measuring outputs to measuring inputs. If you can’t observe the process to improve it, and you can’t figure out how to assess the outputs, you measure and manage the inputs.

Conceptually, if you can’t measure the outputs you can’t measure productivity. This leads to such common management nonsense as rewarding people on how many hours of unpaid overtime they put it or what time they show up in the morning and leave at night. This is marginally defensible if you convince yourself that everyone is producing widgets of roughly equal quality. It seems pretty suspect when you apply it to knowledge work.

This issue becomes more pertinent as the percentage of people in organizations who are knowledge workers grows. When only a handful of your workforce are knowledge workers, you don’t truly care about their productivity. To the extent that you do, you can make qualitative judgments about whether the outputs produced are acceptable.

There is an old tale, probably apocryphal, of Tom Watson at IBM. Showing a fellow CEO around the office, they came across a staffer with his shoes off and feet up on the desk doing nothing. Watson’s guest was outraged and asked why Watson didn’t fire the slacker on the spot (although I wonder what term he used in place slacker). Watson’s answer? “The last idea he had saved IBM $50 million; I’m waiting for the next one.”

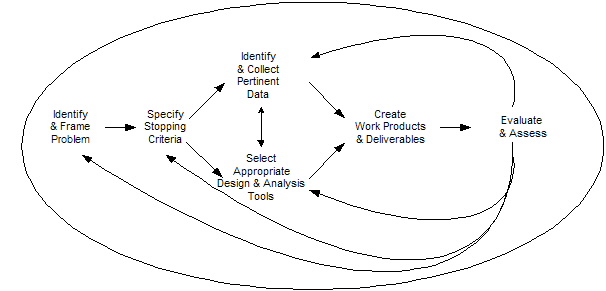

As enlightened a management response as that may be, it isn’t one that scales very well. You need a more systematic approach when substantial numbers of your organization are expected to produce and deliver money saving or money making ideas. Part of this will require us to begin looking at knowledge work as an improvable process.

I’ve begun to entertain the hypothesis that the deliverable is one of the lasting contributions of the consulting profession. Not the bound powerpoint presentation gathering dust on the shelf. But the concept of turning a knowledge work process into some kind of visible result that can be inspected. Once you have something you can inspect, you have something you can begin to manage.

The mistake that gets made is to try to immediately force this into an industrial model. Yes, we can now inspect the result, but we still know very little about its quality. We listen to stale management maxims like “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it” and immediately start counting things because we can, not because it makes any sense. This is a good time to bear in mind Einstein’s observation that “not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.”

There’s plenty of mileage to be gained from some careful observation before we get wrapped up in statistics. The first distinction about knowledge work deliverables as opposed to widgets is that the quality of deliverables is always negotiated and constructed. If the client isn’t happy with the 100-page powerpoint presentation, it isn’t done. If the first three pages answer the question, it is and the remaining 97 are irrelevant.

One of the unfortunate side effects of the various productivity tools made available to us over the past 20 years is that it has become easy to produce what used to be useful indicators of quality (professional type, color diagrams, fancy bindings) without necessarily producing the actual quality. One option is to put your trust in reputation. Certainly, some consultants have raised that to an art form. A better, but more difficult, option is to spend some actual time reviewing the content. If you do take that tack, you’ll find that you want to do that reviewing, evaluating, and negotiating of quality along the way. Otherwise you increase the risk of wasting a lot of expensive time and effort producing the wrong thing.

The challenge here is not simply the change this entails in management style, but also the change it entails in the knowledge worker. If I am producing a deliverable whose quality must be negotiated with the client, I have to take the quite real risk of sharing my thinking before it is complete.

These can be hard habits to break. We’re accustomed to providing and evaluating the “right answer.” Putting an incomplete and still evolving hypothesis out there is risky. Trying to help someone shape that hypothesis into a better one without doing the work yourself is equally hard and frustrating. It’s so much easier to shove the process into a binary one – done/not done.

Weblogs are one useful tool in making this negotiation of quality easier. The format makes it easier to develop ideas in what feel like more manageable chunks.