One unexpected fringe benefit of falling way behind in responding to all the fascinating posts accumulating in your news aggregator is that you get a chance to pull multiple items together into an integrated post. I did one recently on weblogs and knowledge management that a number of people found helpful. The backlog of posts shows no signs of abating, so it's time for a follow up.

Rick Klau sets a nice context by reminding us of Gartner's hype cycle and its application to blogs:

We are almost certainly in the trough of disillusionment when it comes to blogs. Lots of critical comments, much confusion over their “true” benefits, etc. Yet hundreds of thousands of people continue to use their weblog as a way of cataloging their thought. And companies are starting to explore how they might use weblogs for other purposes.

My prediction: we will emerge from this trough into the “slope of enlightenment” during which it will become obvious that personal weblogs can be tremendous tools for capturing ad hoc knowledge and archiving it for future use. Furthermore, businesses will figure out that blogs can serve as both a content management system as well as an internal knowledge sharing platform – a much different use from the personal application, but a critical one for the business world to adopt weblogs with enthusiasm.[tins:::Rick Klau's weblog]

Dina Mehta is relatively new to the blogging world. She offers some helpful fresh perspective on the challenges of introducing weblogs into corporate environments. Thinking about the problems of knowledge management and how weblogs may fit, she says:

I'm not really sure that KM is being adopted in a really useful or effective manner in many organisations here. More importantly, while its great to have a system in place as a talking point, i'm not really sure what real value is being created and disseminated. They tend to be led by the HR department and are usually one-way monologues that not many participate in – (but this is really a topic for another post).

There is a constant generation of content in an organisation – via email, via IM, through documents, presentations, training workshops and seminars, and sometimes through discussion boards. KM systems tend to be slow and heavy in capturing and disseminating this content – in the process, the value may be lost[Conversations with Dina]

Like many of us, she sees that blogs may be the answer, but isn't sure how best to make the case to those in a position to make a decision.

Part of that case will hang on the availability of some concrete examples of weblogs in use in organizations. Two areas that are generating some early examples of weblogs in organizational settings are project management and marketing. Both are naturals for the technology, being high-paced and communications intensive.

On the project management side, Jon Udell at Infoworld is a regular source of good insights into weblogs in organizational settings. Here's a post he ran on the use of weblogs to improve project communications plus the corresponding article at Infoworld (Publishing a Project Weblog).

The value of a project Weblog has a lot to do with getting everybody onto the same page — literally. You want to deliver a manageable flow on the home page, drawing attention to the key events in the daily life of the project. To do this well, think like a journalist. …

The newspaper editor's mantra is “heads, decks, and leads” — in other words, headlines, summaries, and introductory paragraphs. These devices are, in fact, tools for managing a scarce and precious resource: the reader's attention. A well-written title (or subject header if you happen to be composing an e-mail message) is your first, best, and often only chance to get your message across.

There's a particularly useful diagram Jon reproduces in another Infoworld post on blogs, scopes, and human routers and drawn from his his equally useful book, Practical Internet Groupware. It captures a notion of the multiple overlapping groups that we belong to in the pursuite of knowledge work.

Jon has also talked about the notion of what he calls the conversational enterprise and how weblogs will serve as a key source of the raw materials for knowledge management in organizations (Technical trends bode well for KM);

What k-loggers do, fundamentally, is narrate the work they do. In an ideal world, everyone does this all the time. The narrative is as useful to the author, who gains clarity through the effort of articulation, as it is to the reader. But in the real-world enterprise, most people don't tend to write these narratives naturally, and the audience is not large enough to inspire them to do it.

There is, however, a certain kind of person who has a special incentive to tell the story of a project: the project managers, who are among the best power users of Traction Software's enterprise Weblogging software, according to “Traction” co-founders Greg Lloyd and Chris Nuzum (see “Getting Traction”).

“Traction” certainly is powerful software, although the power does come at the expense of a somewhat steeper learning curve than systems like “Radio” or Moveable Type whose origins were in personal weblogs rather than enterprise. Actually, it might be better to think in terms of a steeper implementation curve, rather than learning curve. Setting up “traction” in terms of project structures and tags takes some thought to get full advantage of the tools. Using them on a day-to-day basis is pretty straightforward.

The use of weblogs in marketing settings is also drawing attention. Some of that is in the form of early, and rightfully ridiculed, examples such as the faux-blog Raging Cow, which tried to force its traditional marketing strategy through a blog format.

Others have made more sensible progress (I suppose that makes me terminally boring). Inc. Magazine ran a recent piece on Blogging for Dollars (link found via Blogging News), for example, that highlights some examples of the real use of blogs as a marketing tool.

Gary Murphy at TeledyN offers up a couple of interesting examples of KM in organizational settings in a recent post on Walmart's KM rocks.

Both searches were initially pointless because, for very good reasons, both the sought after data items did not exist in the superficially logical locations. This is probably the number one flaw with most dead-robot KM systems: They fail to accommodate how Reality is inherently messy!

The only possible method to locate either the ribs or the cards was to do what humans have done since the dawn of archives, ask someone who knows. In both instances, we needed someone who knew where the target was, and who could refer us to someone who knew how to extract it.

Murphy provides the critical link here between weblogs and organizational need. It is the realization that KM in organizational settings is primarily a social phenomenon and not a technology one. Most prior efforts to apply technology to KM problems in organizations have been solutions in search of a problem. They have been driven by a technology vendor's need to sell product, not an organization's need to solve problems.

Weblogs are interesting in organizational KM settings because weblogs are technologically simple and socially complex, which makes them a much better match to the KM problems that matter. One thing that we need to do next is to work backwards from the answer – weblogs – to the problem – what do organizations need to do effective knowledge management. We need to avoid the mistakes of other KM software vendors and not assume that the connection is self-evident.

Now this is how to advertise your local by-laws.

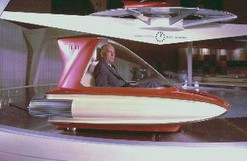

Now this is how to advertise your local by-laws.  Yesterday's Tomorrows is a nice web-exihibit of the used-to-once-wasses that never were.

Yesterday's Tomorrows is a nice web-exihibit of the used-to-once-wasses that never were.